State of AI in November by the author: Geopolitics, Diplomacy, and Governance

Will the AI bubble burst? Is AI now ‘too big to fail’? Will the U.S. government bail out AI giants – and what would that mean for the global economy?

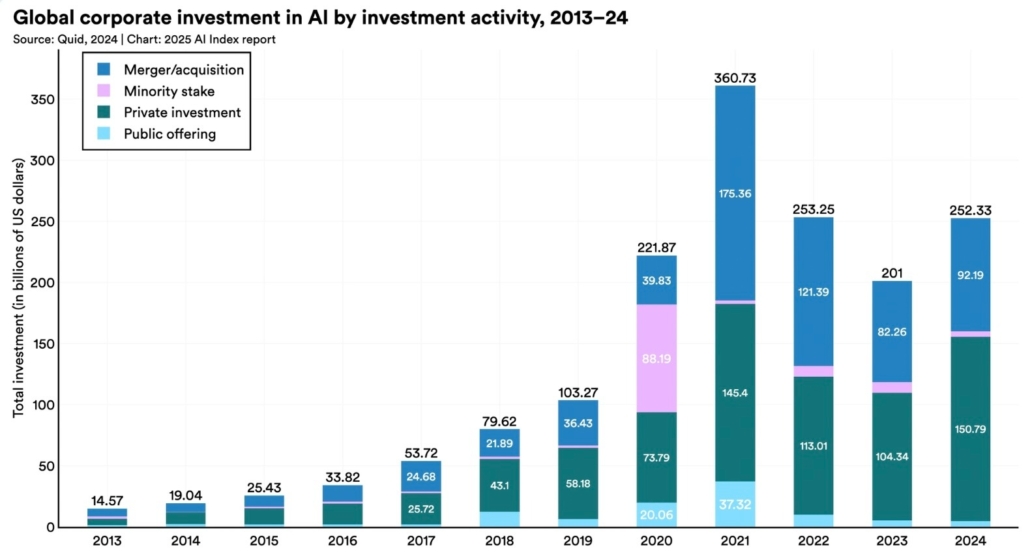

These questions are now everywhere in the media, boardrooms, and policy circles. Corporate AI investment hit around $252 billion in 2024 – more than 13× higher than a decade ago – while the global AI market is projected to jump from about $189 billion in 2023 to nearly $4.8 trillion by 2033.

Source: Stanford HAI+1

At the same time, many companies struggle to turn pilots into profit. The gap is widening between, on the one hand, AI hype, trillion-dollar valuations, and massive infrastructural spending, and on the other hand, the slower business and societal reality of AI adoption.

This post examines five primary causes of a potential AI bubble and explores five scenarios for how the world might prevent – or cope with – a potential burst. It then sketches the likely role of five key players.

Five causes of the AI bubble

The frenzy of AI investment did not happen in a vacuum. Several forces have contributed to our tendency toward overvaluation and unrealistic expectations.

1st cause: The media hype machine

AI has been framed as the inevitable future of humanity – a story told in equal parts fear and awe. This narrative has created a powerful Fear of Missing Out (FOMO), prompting companies and governments to invest heavily in AI, often without a sober reality check. The result:

- Corporate AI investment has reached record levels, with more than $250 billion invested in 2024 alone.

- Big Tech is raising close to $100 billion in new debt for AI and cloud infrastructure, with data-centre spending expected to reach roughly $400 billion in a single year.

- AI chipmaker Nvidia briefly hit a $5 trillion market capitalisation in 2025 – more than 12× its value at the launch of ChatGPT – and still dominates the AI hardware landscape.

Market capitalisation of AI-exposed companies is now measured in multi-trillion-dollar chunks. Nvidia alone has been valued in the $4–5 trillion range, comparable to the combined annual GDP of many regions. Hype has often run ahead of business logic: investments are driven less by clear use cases and more by the fear of being left behind.

2nd cause: Diminishing returns on computing power and data

The dominant, simple formula of the past few years has been:

More compute (read: more Nvidia GPUs) + more data = better AI.

This belief has led to massive AI factories: hyper-scale data centres and an alarming electricity and water footprint. Yet we are already hitting diminishing returns. The exponential gains of early deep learning have flattened.

Simply stacking more GPUs now yields incremental improvements, while costs rise super-linearly and energy systems strain to keep up. The AI paradigm is quietly flipping: practical applications, domain knowledge, and human-in-the-loop workflows are becoming more important than raw compute at the base.

3rd cause: LLMs’ logical and conceptual limits

Large language models (LLMs) are encountering structural limitations that cannot be resolved simply by scaling data and compute. Despite the dominant narrative of imminent superintelligence, many leading researchers are sceptical that today’s LLMs can simply be ‘grown’ into human-level Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). Meta’s former chief AI scientist, Yann LeCun, put it this way:

On the highway toward human-level AI, a large language model is basically an off-ramp — a distraction, a dead end.

LLMs are excellent pattern recognisers, but they still:

- hallucinate facts;

- struggle with robust long-horizon planning;

- lack a grounded understanding of the physical world.

Future neural architectures will certainly improve reasoning, but there is currently no credible path to human-like general intelligence that consists simply of ‘more of the same LLM, but bigger.’

4th cause: Slow AI transformation

Most AI investments are still based on potential, not on realised, measurable value. The technology is advancing faster than society’s ability to absorb it. Organisations need time to:

- redesign workflows and business processes;

- change procurement and risk models;

- retrain workers and managers;

- adapt regulation, liability, and governance frameworks.

Emerging evidence is sobering:

- BCG finds that around 74% of companies struggle to achieve and scale value from AI initiatives.

- An MIT-linked study reported that roughly 95% of generative AI pilots fail to generate a meaningful business impact beyond experimentation.

The time lag between technological capability and institutional change is a core risk factor for an AI bubble. There is no shortcut: social and organisational transformation progresses on multi-year timescales, regardless of how fast GPUs are shipped.

History reminds us what happens when hype outruns reality. Previous AI winters in the 1970s and late 1980s followed periods of over-promising and under-delivering, leading to sharp cuts in funding and industrial collapse.

5th cause: Massive cost discrepancies

The latest wave of open-source models has exposed a startling cost gap. Chinese developer DeepSeek reports that:

- DeepSeek-V3 costs around $5.5 million to train on 14.8 trillion tokens.

- Its more recent inference-focused R1 model reportedly cost $294,000 to train – yet rivals top Western systems on many reasoning benchmarks.

By contrast:

- Analysts estimate that training frontier models like GPT-4.5 or GPT-5-class systems can cost on the order of $500 million per training run.

This 100-to-1 cost ratio raises brutal questions about the efficiency and necessity of current proprietary AI spending. If open-source models at a few million dollars can match or beat models costing hundreds of millions, what exactly are investors paying for?

It is in this context that low-cost, open-weight models, especially from China, are reshaping the competitive landscape and challenging the case for permanent mega-spending on closed systems.

Five possible scenarios: what happens next?

AI is unlikely to deliver on its grandest promises – at least not on the timelines and business models currently advertised. More plausibly, it will continue to make marginal but cumulative improvements, while expectations and valuations adjust. Here are five plausible scenarios for resolving the gap between hype and reality. In practice, the future will be some mix of these.

1st Scenario: The rational pivot (the textbook solution)

The classic economics textbook response would be to revisit the false premise that “more compute automatically means better AI” and instead focus on:

- smarter architectures;

- closer integration with human knowledge and institutions;

- smaller, specialised, and open models.

In this scenario, AI development pivots toward systems that are:

- grounded in curated knowledge bases and domain ontologies;

- tightly integrated with organisational workflows (e.g. legal, healthcare, diplomacy);

- built as open-source or open-weight models to enable scrutiny and reuse.

This shift is already visible in policy. The U.S. government’s recent AI Action Plan explicitly encourages open-source and open-weight AI as a strategic asset, framing ‘leading open models founded on American value’ as a geostrategic priority.

However, a rational pivot comes with headwinds:

- entrenched business models built on closed IP;

- corporate dependence on proprietary data and trade secrets;

- conflicts over how to reward creators of human-generated knowledge.

A serious move toward open, knowledge-centric AI would immediately raise profound questions about intellectual property law, data sharing, and the ownership of the ‘raw material’ used to train these systems.

2nd Scenario: “Too big to fail” (the 2008 bailout playbook)

A different path is to treat AI not just as a sector but as critical economic infrastructure. The narrative is already forming:

- Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai has warned that there are clear ‘elements of irrationality’ in current AI investment, and that no company – including Google – would be immune if an AI bubble burst.

- Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang has joked internally that if Nvidia had delivered a visibly weak quarter, ‘the whole world would’ve fallen apart,’ capturing the sense that markets have come to see Nvidia as holding the system together.

If AI is framed as a pillar of national competitiveness and financial stability, then AI giants become ‘too big to fail’. In other words:

If things go wrong, taxpayers should pick up the bill.

In this scenario, large AI companies would receive explicit or implicit backstops – such as cheap credit, regulatory forbearance, or public–private infrastructure deals – justified as necessary to avoid broader economic disruption.

3rd Scenario: Geopolitical justification (China ante portas)

Geopolitics can easily become the master narrative that justifies almost any AI expenditure. Competition with China is already used to argue for:

- massive public funding of AI infrastructure;

- strategic partnerships between government, cloud providers, and foundation-model companies;

- preferential treatment for ‘national champions’.

The U.S. now frames open models and open-weight AI as tools of geopolitical influence, explicitly linking them to American values and global standards.

At the same time, China is demonstrating that low-cost, open-source LLMs, such as DeepSeek R1, can rival Western frontier models, sparking talk of a ‘Sputnik moment’ for AI.

In this framing, a bailout of AI giants is rebranded as:

an investment in national security and technological sovereignty.

Risk is shifted from private investors to the public, justified not by economic considerations but by geopolitical factors.

4th Scenario: AI monopolisation (the Wall Street gambit)

As smaller players run out of funding or fail to monetise, AI capacities could be aggressively consolidated into a handful of tech giants. This would mirror earlier waves of monopolisation in:

- social media (Meta);

- search and online ads (Google);

- operating systems and productivity (Microsoft);

- e-commerce and cloud (Amazon).

Meanwhile, Nvidia already controls roughly 80–90% of the AI data-centre GPU market and over 90% of the training accelerator segment, making it the de facto hardware monopoly underpinning the entire stack.

In this scenario:

- Thousands of AI start-ups and incubators shrink to a small layer of niche providers.

- A few proprietary platforms dominate: Google, Microsoft, Meta, Amazon, Apple, plus Nvidia at the hardware layer.

- These firms add an AI layer to existing products – Office, Windows, Android, iOS, search, social networks, retail – making it easier for businesses and users to adopt AI inside closed ecosystems.

The main risk is a new wave of digital monopolisation. Power would shift even more decisively from control over data to control over knowledge and models that sit atop that data.

Open-source AI is the main counterforce. Low-cost, bottom-up development makes complete consolidation difficult, but not impossible: large firms can still dominate by owning the distribution channels, cloud platforms, and hardware.

5th Scenario: AI winter and new digital toys

The digital society appears to require a permanent “frontier technology” to focus attention and capital. Gartner’s hype-cycle metaphor captures this: technologies surge from a “peak of inflated expectations” to a ‘trough of disillusionment’ before stabilising – often over 5–10 years.

We have seen this before:

- Expert systems and LISP machines in the 1980s;

- The “AI winters” of the 1970s and 1990s;

- More recently, blockchain, ICOs, NFTs, and the Metaverse.

AI has already lasted longer at the top of the hype cycle than many of those digital “toys”. In this scenario, we would see:

- a mild AI winter: slower investment, consolidation, less media attention;

- capital rotating toward the next frontier – likely quantum computing, digital twins, or immersive virtual and mixed reality;

- AI remains an important infrastructure, but no longer the primary object of speculative enthusiasm.

The global frontier-tech market will remain enormous, but AI will share the spotlight with new innovations and narratives.

Main actors: Strengths and weaknesses

OpenAI

Strengths: ChatGPT is still the most recognisable AI brand globally. OpenAI claims hundreds of millions of weekly active users; external estimates put that figure in the 700–800 million range in 2025, with daily prompt volumes in the billions.

OpenAI also enjoys:

- tight integration with Microsoft’s ecosystem (Azure, Windows, Office);

- a strong developer platform (API, fine-tuning, marketplace);

- a first-mover advantage in consumer awareness.

Weaknesses: OpenAI is highly associated with the most aggressive AI hype – including its CEO’s focus on AGI and existential risks. It is structurally dependent on:

- expensive frontier-model training and inference;

- Nvidia’s hardware roadmap;

- continued willingness of investors and partners to fund the infrastructure build-out.

OpenAI’s revenue remains overwhelmingly tied to AI services (ChatGPT subscriptions, API usage). OpenAI is unlikely to generate revenue by 2030 and still requires an additional $207 billion to fund its growth plans, according to HSBC estimates.

In a bubble-burst scenario, OpenAI is a prime candidate to be restructured rather than destroyed:

- It could survive by leaning heavily into a geopolitical narrative, positioning itself as a national-security asset and securing U.S. government and defence-related funding.

- More likely, it would be pulled fully into the Microsoft family, becoming a deeply integrated (and more tightly controlled) division rather than a semi-independent partner.

Google (Alphabet)

Strengths: Alphabet has the most vertically integrated AI lifecycle:

- In-house chips (TPUs) are increasingly sold externally;

- frontier models (Gemini series, other foundation models);

- a global distribution network (Search, YouTube, Android, Chrome, Gmail, Maps, Workspace, Cloud).

Its market capitalisation is racing toward $4 trillion on the back of AI optimism, with Gemini 3 seen as a credible rival to OpenAI’s and Anthropic’s top models. (Source: Reuters)

Weaknesses:

- The company’s caution culture and regulatory scrutiny can slow product launches.

- AI that truly answers questions may cannibalise the very search-ad business that still funds much of Alphabet.

- Heavy reliance on cloud and advertising makes it exposed to any macroeconomic slowdown.

Yet among the big players, Google may be best positioned to weather a bubble burst because AI is layered across an already profitable, diversified portfolio rather than being the core business itself.

Meta

Strengths: Meta has pursued an aggressive open-source strategy with its Llama family of models. Llama has become the default base for thousands of open-source projects, start-ups, and enterprise deployments. Meta also controls:

- three of the world’s biggest social platforms (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp);

- a sophisticated advertising and recommendation stack;

- Reality Labs and VR/AR efforts that could integrate deeply with generative models.

This mix enables Meta to ship AI features at scale – from AI assistants in messaging apps to generative tools in Instagram – while utilising open weights to shape the ecosystem in its favour.

Weaknesses:

- Business remains overwhelmingly ad-driven, making it vulnerable to macroeconomic shocks and regulatory limitations on tracking and targeting.

- Its Metaverse investments remain controversial and capital-intensive.

- Regulators in the EU and elsewhere closely monitor Meta for compliance with privacy, competition, and content governance standards.

Meta is less dependent on selling AI as a product and more focused on using AI to deepen engagement and ad performance, which may make it more resilient in a correction.

Microsoft

Strengths: Microsoft made the earliest and boldest bet on OpenAI, embedding its models across Windows, Office (via Copilot), GitHub (Copilot for developers), and Azure cloud services. This gives Microsoft:

- unmatched enterprise distribution for AI tools;

- leverage to push AI into government, defence, and regulated industries;

- a leading position in AI-heavy cloud workloads.

Together with other giants, Microsoft is part of a club expected to invest hundreds of billions of dollars in data centres and AI infrastructure over the next few years.

Weaknesses:

- Heavy dependence on OpenAI’s technical roadmap and on Nvidia’s chips.

- Enormous capital expenditure that may be difficult to justify if AI monetisation stalls.

- Growing antitrust risks as AI is woven into already dominant products.

In a mild bubble burst, Microsoft is more likely to reshuffle its partnerships than to retreat from AI: OpenAI could be integrated more closely, while Microsoft simultaneously accelerates its own in-house models.

Nvidia

Strengths: Nvidia has become the picks-and-shovels provider of the AI gold rush:

- controlling around 80–90% of the AI chip and data-centre GPU market;

- reaching a $5 trillion valuation at its peak in 2025;

- enjoying gross margins above 70% on some AI products.

Its CUDA software ecosystem and networking stack form a moat that competitors (AMD, Intel, Google TPUs, Amazon chips, Huawei and other Chinese challengers) are still struggling to cross.

Weaknesses:

- Extreme dependence on one story: ‘AI keeps scaling up.’

- Heavy exposure to export controls and U.S.–China tensions, with Chinese firms both stockpiling Nvidia chips and racing to build alternatives.

- Customer concentration risk: A handful of hyperscalers and model labs account for a significant share of demand.

In a scenario where the emphasis shifts from brute-force computing power to smarter algorithms and better data, Nvidia would still be central – but its growth and margins could come under serious pressure.

The critical battle: Open vs Proprietary AI

The central tension in AI is no longer purely technical. It is philosophical:

Centralised, closed platforms vs. decentralised, open ecosystems.

On one side:

- proprietary frontier models;

- tightly controlled APIs;

- vertically integrated cloud + chip + model stacks.

On the other:

- open-source or open-weight models (Llama, DeepSeek, Mistral, etc.);

- community-driven tooling and evaluation;

- local and specialised deployments outside big-cloud walled gardens.

Historically, open systems often win in the long run – think of the internet, HTML, and Linux. They become standards, attract ecosystems, and exert pressure on closed incumbents.

Two developments are especially telling:

- China’s strategic embrace of open-source AI: Chinese labs, such as DeepSeek, utilise open weights and aggressive cost reduction to challenge U.S. dominance, turning open models into a geopolitical play.

- The U.S. pivot toward open models in official policy: America’s AI Action Plan explicitly calls for ‘leading open models founded on American values’ and strongly encourages open-source and open-weight AI as a way to maintain technological leadership and set global standards.

As tech giants remain slow and reluctant to fully embrace open-source, a future crisis could give governments leverage:

Any bailout of AI giants could be conditioned on a mandatory shift toward open-weight models, open interfaces, and shared evaluation infrastructure.

Such a deal would not just rescue today’s players; it would amount to a strategic reset, nudging AI back toward the collaborative ethos that powered the early internet and many of the great US innovations.

What is going to happen? A crystal-ball exercise

Putting it all together, a plausible outlook is:

- No dramatic global crash, because the systemic risk is now too large. AI is tightly woven into stock indices, sovereign wealth portfolios, and national strategies.

- A series of smaller “pops” hitting the most over-extended frontier-model players and speculative start-ups.

In this view:

- The main correction falls on OpenAI and Anthropic (Claude) and similar labs, whose valuations and burn rates are hardest to justify. They do not disappear; they are folded into larger ecosystems. OpenAI could become a Microsoft division; Anthropic could plausibly end up with Apple, Meta, or Amazon.

- Nvidia is another likely loser relative to its peak valuation. As the focus shifts from sheer computing power to smarter algorithms, open-source models, and improved data, the market may reassess the notion that every AI advance requires another order of magnitude of GPUs – especially as Google, AMD, custom ASICs, and domestically produced Chinese chips become more competitive.

- The biggest winner of a small AI bubble burst could be Google. It has the most integrated AI lifecycle (from chips and models to consumer and enterprise applications) and strong cash flow from mature businesses. Among Big Tech, it may be best placed to ride out volatility and consolidate gains.

The main global competition will increasingly be between proprietary and open-source AI solutions. Ultimately, the decisive actor will be the United States that faces a fork in the road:

- Double down on open-source, as signalled in the AI Action Plan, treating open models, shared datasets, and public infrastructure as strategic assets.

- Slide back into supporting AI monopolies, whether via trade agreements, security partnerships with close allies, or opaque public-private mega-deals that effectively guarantee the revenues of a few AI and cloud giants.

The AI bubble will not be decided only by markets or by technology. It will be decided by how societies choose to balance:

- open vs proprietary;

- national security vs competition;

- short-term financial stability vs long-term innovation.

The next few years will show whether AI becomes another over-priced digital toy – or a more measured, open, and sustainable part of our economic and political infrastructure.

Click to show page navigation!