History of diplomacy and technology: From smoke signals to artificial intelligence (2nd edition)

Ever wonder how ancient messengers shaped today’s AI-driven diplomacy? Or why a 15th-century printing press still echoes in modern disinformation wars? To understand the forces that define how technology drives power today, we first need to understand yesterday’s breakthroughs.

The book explores 5,000 years of interaction between diplomacy and technology. From the invention of writing to algorithms in contemporary foreign ministries, this research traces how technological advances have shaped diplomatic practice and influenced global affairs.

In this book, Jovan Kurbalija shows why today’s tech disruptions are less ‘unprecedented’ than we often think. On 400 pages, supported by extensive footnotes and detailed tables and illustrated with figures and maps, the book is perfect reading for:

• diplomats navigating digital fragmentation;

• tech pioneer building governance frameworks;

• historians rethinking societal evolution;

• anyone exhausted by shallow ‘tech will save/destroy us’ takes.

BOOK REVIEW

Book review by Prof. Geoff Berridge

Methodologically inspired by the French Annales School of historiography and determinedly reaching beyond Europe, the author of this book has nevertheless produced a work that has rarely sacrificed important detail to breadth of focus.

Its general thesis is that the evolution of diplomacy has been shaped by three great technological inventions: writing, electricity and digitalization, and each is examined in turn. It is a work of considerable authority: carefully sourced and argued, as well as being fluent, rich in intriguing facts, tightly organized, and illustrated with beautiful and often intriguing pictures.

It is a genuine tour de force. Although aimed chiefly at young professional diplomats, it can be read with advantage by older ones and will be of great value to historians of the subject as well.

AI agent for the book

A masterpiece of longue durée scholarship. Finally, a map for our disorienting technological age.

Pre-release academic reviewer

Consult the table of contents

Table of contents

| Preface |

| Introduction: A methodological toolkit for analysing the co-evolution of diplomacy and technology |

| Part I | Foundations: Language, messengers, and trust |

| Chapter 1 | The dawn of diplomacy: From oral traditions to written communication |

| Chapter 2 | Empires and messengers: Organised diplomacy in the ancient world |

| Chapter 3 | Wider worlds of diplomacy: Patterns of power and protocol in ancient civilisations |

| Part II | Pillars of diplomacy: From the polis to the imperial court |

| Chapter 4 | Envoys of the polis: The art of diplomacy in classical Greece |

| Chapter 5 | Rule and reach: Diplomacy as strategy in the Roman Empire |

| Chapter 6 | The Byzantine synthesis: Ceremony, intelligence, and information control |

| Part III | Crossroads of faith, empire, and state: From sacred authority to secular power |

| Chapter 7 | Shepherds of influence: Papal diplomacy in Medieval Europe |

| Chapter 8 | Islamic Golden Age: Trade, faith, and political strategy across the desert |

| Chapter 9 | The Renaissance revolution: Printing, permanent embassies, and public opinion |

| Chapter 10 | The Age of Cabinets: Cryptography, communication security, and the rise of foreign ministries |

| Part IV | The shrinking world: Communication, conflict, and coordination in the electric era |

| Chapter 11 | The electric current: Telegraphy, instant communication, and crisis diplomacy |

| Chapter 12 | The telephone: Voice communication across distance |

| Chapter 13 | Wireless and radio: Shaping public diplomacy and propaganda |

| Chapter 14 | Visual power: Television and film in wars and diplomacy |

| Part V | The digital frontier: Connectivity, complexity, and the rise of artificial intelligence |

| Chapter 15 | Diplomacy on the net: The digital transformation of diplomatic practice |

| Chapter 16 | The cognition and compromise: Diplomacy in the AI era |

| Conclusion: The enduring continuity and change of diplomacy and technology |

| The three revolutions revisited: Synthesising the historical trajectory |

| Constants of statecraft: Lessons from the longue durée |

| The next frontier: Navigating cognitive proximity in the AI era |

| References |

| Index |

| List of figures |

| List of maps |

| List of tables |

| About the author |

Preface

Whenever we hear claims that AI or any technology will replace diplomacy, we should remember that the printing press, the telegraph, and the radio were each once seen as existential threats to statecraft. Yet diplomacy survived each of those disruptions not by resisting technological progress, but by adapting to it.

This tension between technological change and diplomatic continuity is the central theme of this book. It raises a question that has followed me for decades: How has diplomacy adapted to technological shifts throughout history? From ancient gift-giving to algorithmic diplomacy, one refrain echoes across time: What changed? What remained? And what wisdom can we carry forward?

My own search for an answer began in 1990, when I joined diplomacy and found myself caught between two eras: one shaped by centuries-old rituals of in-person negotiation, the other quietly emerging through the glow of email and digital databases. I watched senior colleagues dismiss the rise of email as a distraction, even as younger diplomats like myself sensed that our profession was on the verge of transformation.

Read more

The quest became more focused during an academic sabbatical in 1991. While researching the future of AI in international law, I realised something unexpected: the more I explored new technologies, the more I understood the enduring relevance of diplomacy’s core functions: representation, negotiation, and compromise.

I soon experienced this insight in a very personal way. While I was studying diplomacy’s past and future, my own country, Yugoslavia, was dissolving into war. This traumatic experience taught me firsthand that states are temporary social constructs we create to organise our collective life. Yet even as nations fractured, the first thing newly formed entities did was establish diplomatic services. It was a profound lesson: governments and borders may be fleeting, but the human need to engage, represent, and seek peaceful resolution is constant.

Diplomacy is more than limousines and flags; at its core, it reflects a much deeper drive, the one that began when our distant ancestors discovered it was better to talk than to kill one another. Technologies have continuously evolved from smoke signals to satellites, but that fundamental mission has remained the same.

History, of course, is no oracle. It won’t hand us a step-by-step guide to the future. But it does give us something just as important: perspective. In the pages ahead, I trace patterns of adaptation, offering cautionary tales of hubris and inspiring stories of ingenuity, to shed light on our current crossroads.

This book is neither a eulogy for tradition nor a manifesto for disruption. It is a plea for balance. As we race toward a future shaped by AI, we must carry forward the wisdom of those who navigated similar tides before us. The tools will keep evolving, but diplomacy’s mission – to represent, engage, and seek common ground in a world of constant change – remains.

Acknowledgement

A project of this depth is never a solitary endeavour; it grows from the generosity, guidance, and support of many. My deepest gratitude goes first to my wife, Aleksandra, whose unwavering patience and brilliant insights anchored me through every challenge. Her belief in this work gave me the courage to persist and the confidence to carry it forward.I am equally indebted to the vibrant community of Diplo’s students, researchers and lecturers who broadened my perspective and opened windows into the richness of Asian, African, and Indigenous diplomatic traditions.

Their engagement and curiosity continually reminded me of the global fabric within which this work is woven. Special thanks are due to Mina Mudrić, whose steady commitment and sharp instincts helped reignite momentum at crucial moments. For this edition, I owe much to Dina Hrecak, whose thoughtful editing polished each page with care; to Ivana Dunjić, whose meticulous research strengthened the book’s foundations; and to Sorina Teleanu, whose keen eye refined its essence with clarity and precision.

Jovan Kurbalija

Geneva, 21 July 2025

Book methodology

A methodological toolkit for analysing the co-evolution of diplomacy and technology

No single historical, sociological, or technical research methodology can fully capture the interplay between diplomacy and technology across disciplines and time.

A purely historical approach could end in a catalogue of events and inventions, while a strictly technological lens can fall into the trap of determinism, treating diplomacy as a passive follower of technological changes.

Thus, this research nurtured a 3x3x3 methodology centred around three technologies (writing, electric, digital), three time dynamics (immediate events, medium trends, long-term shifts), and three themes (geopolitics, topics on diplomatic agenda, and tools for diplomacy.

Read more

The study’s 3×3×3 methodology serves not as a rigid formula, but as a heuristic device. This allows for a systematic yet flexible exploration of the tension between change and continuity that defines the history of diplomacy and technology.

TIME: Three temporal aspects in the evolution of technology and diplomacy

The temporal framework of the book is inspired by the Annales School historian Fernand Braudel, centred around three layers of historical time: specific events (événement), trends of the era (conjoncture), and structural dynamics (longue durée).

This layered temporal methodology helps avoid the risk of shallow focus on the surface historical level of events, individuals, and anecdotal accounts, typical of diplomatic history.

Événement: The surface events as historical laboratories

The événement is the surface layer of history, comprising specific, short-term events including battles, treaties, and major conferences.

While Braudel cautioned against overemphasising the relevance of specific historical moments, this study treats them as ‘historical laboratories’ where the deeper forces of the longue durée and conjoncture become visible and their effects can be tangible.

For instance, the Treaty of Kadesh (1259 BCE) is not just a singular peace agreement but an événement that reveals the mature diplomatic conjoncture of the Bronze Age, with its emphasis on written accords, divine witnesses, and parity between great powers.

Similarly, the Ems Telegram incident of 1870 is a powerful case study demonstrating the electric conjoncture’s new perils, where the telegraph’s speed could be misused to bypass deliberation and ignite conflict, as Prussian Chancellor Bismarck did.

The 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis was a critical événement triggering the establishment of the Moscow-Washington hotline, allowing for direct communication between superpower leaders to deal with the crisis.

Conjoncture: The rhythms of change

The conjoncture is the medium-term layer of history, capturing the cyclical shifts in economic, social, and technological systems that unfold over decades or centuries. This temporal lens identifies distinct diplomatic eras, each defined by a prevailing set of technologies, political structures, and international norms.

For example, the Late Bronze Age was characterised by the Amarna system, a sophisticated diplomatic culture built on a shared lingua franca (Akkadian cuneiform), regular royal correspondence, and a balance of power among the great empires of the Near East.

Later, the Renaissance in Europe marked a new conjoncture, where the rise of the modern state system was facilitated by the printing press, which helped forge national identities, and the invention of the permanent resident embassy triggered institutionalisation of diplomacy.

The 19th and early 20th centuries constituted the electric era, a conjoncture defined by imperial competition and instantaneous global communication enabled by the telegraph and radio.

Today, we are in another turbulent conjoncture transition, moving from the internet era, based on the transmission control protocol/internet protocol (TCP/IP), into an AI era centred around the automation of access to knowledge and the augmentation of human cognition.

Longue durée: The deep constants of statecraft

The longue durée is the deepest and slowest-moving historical layer, spanning centuries or millennia. Geography, deep-seated cultural norms, and fundamental human impulses shape societies over vast periods.

In the context of this book, the longue durée illuminates what remains constant in statecraft, even as the technological landscape is radically transformed. The most profound constant is the human drive for survival through dialogue as an alternative to violence, an impulse visible from the earliest forms of proto-diplomacy, such as prehistoric gift exchanges designed to build trust and reciprocity between tribes.

This same impulse is echoed in the reconciliation rituals observed in primate societies, suggesting its roots run deeper than human history itself.

Geography’s influence remains stubbornly consistent across time. Digital submarine cables, for instance, often retrace the paths of early telegraph lines and even ancient sea navigation routes. Historically, locations like Gibraltar, Suez, Malacca, and Ormuz have maintained their critical geographical importance on humanity’s political, trading, and communication maps.

Another enduring feature in diplomacy’s history is the messenger’s sanctity. The inviolability of the Greek keryx, who could traverse battle lines under divine protection, is an early formalisation of a norm that persists in the modern principle of diplomatic immunity, codified in the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. This principle underscores a timeless requirement of diplomacy: for communication to occur, the channel must be secure and the messenger safe.

Furthermore, the longue durée reveals the persistent necessity of uniquely human qualities for diplomacy, like empathy, intuition, and trust. Even in an era of AI-assisted negotiations, these attributes remain irreplaceable for building rapport, understanding unspoken intentions, and forging genuine compromise.

TECHNOLOGY: Writing, electricity, and digitalisation in the evolution of communication and information

Writing, electricity, and digitalisation are three technologies that have fundamentally altered key pillars of diplomacy: communication, information, and knowledge.

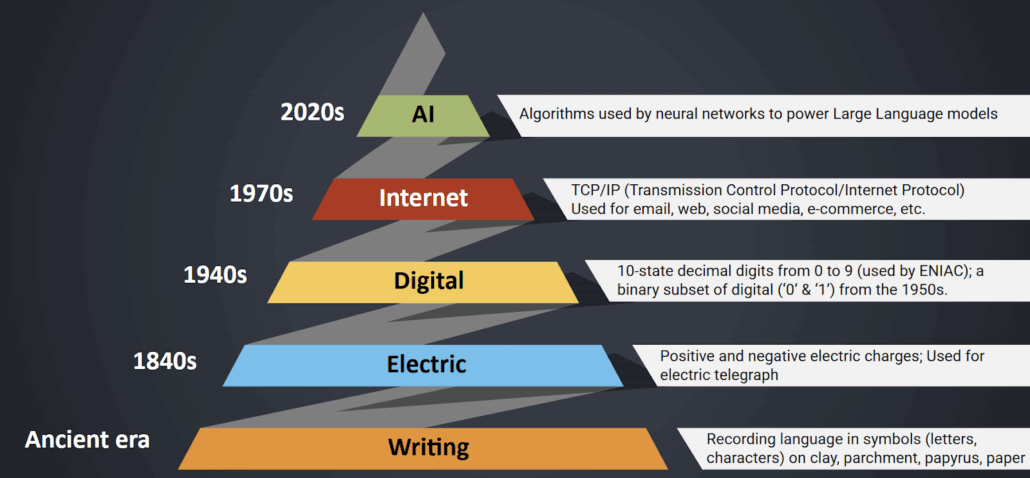

Figure 1: Evolution of technology from writing to AI

Each technology revolution introduced new forms of communication infrastructure (the physical means of communication) and new information management methods (the systems for organising, securing, and utilising data and information).

Writing, electricity, and digitalisation have altered ‘proximity’ in diplomacy related to the relationship between diplomats, their capitals, and the global public.

First revolution: Writing and archives

The invention of writing transformed diplomacy from a practice reliant on verbal communication and fallible human memory into one grounded in permanent, verifiable records. This shift from oral to literate culture laid the foundations for organised statecraft.

- Infrastructure: The first networks were built to carry written messages across vast territories, such as the organised courier relays of ancient Mesopotamia, the magnificent Persian Royal Road stretching from Sardis to Susa, the extensive road system of the Roman Empire, and the remarkably efficient chasqui runner system of the Inca Empire. These networks were the arteries of imperial administration and diplomatic communication.

- Knowledge management: Writing enabled new ways to capture and organise knowledge and information of critical relevance for diplomacy. The creation of archives, like the collection of cuneiform tablets known as the Amarna Letters, provided institutional memory, allowing rulers to reference past agreements and maintain continuity in foreign relations.

- Proximity: Writing did not reduce physical and cognitive distance. Envoys and ambassadors operated with significant autonomy, as courier instructions could take weeks or months to arrive. This distance provided a natural buffer for deliberation and on-the-ground decision-making.

Second revolution: Electricity and the annihilation of distance

The invention of electrical technologies sparked the second revolution, which led to the invention of the telegraph, telephone, and radio. This era was defined by the near-instantaneous transmission of information, effectively annihilating the constraints of distance that had shaped diplomacy for millennia.

- Infrastructure: In this era, networks became electrical, centred on the vast web of submarine telegraph cables that encircled the globe, epitomised by Britain’s ‘All Red Line,’ which connected its empire without reliance on foreign powers. Telegraph cables later started carrying telephone voice messages. Another major shift was the use of radio communication that bridged the distance across continents.

- Knowledge management: Knowledge and information became central. The ability to intercept and decode enemy communications became a decisive strategic advantage. The speed of electrical communication created new challenges for securing information.

- Proximity: The telegraph introduced operational proximity between the foreign ministry and its ambassadors, dramatically reducing their autonomy and centralising control. The ambassador was now at ‘the end of the wire’ waiting for instructions from the capital.

The telephone added vocal proximity, allowing for the direct transmission of information, tone, and emotions. The telephone was critical in de-escalating crises between the United States and the Soviet Union by using the Moscow-Washington hotline.

Finally, radio and television created public proximity, presenting foreign events in real time to national audiences and adding the domestic public as another critical aspect of diplomacy.

Third revolution: Digitalisation and the augmentation of cognition

The third revolution, which we live through, is driven by digitalisation and the rise of AI. This shift is moving beyond the mere processing of information to the automation of knowledge and the augmentation of human cognition.

- Infrastructure: The infrastructure of the digital age is a complex, layered ecosystem. It includes the physical internet backbone of fibre-optic cables, a new generation of satellite constellations providing global connectivity, and the massive cloud data centres that store the world’s information and powerful AI models.

- Knowledge management: Digitalisation has transformed knowledge management. Diplomacy now relies on vast databases, social media analytics, and sophisticated data processing. AI is taking this further, with models that can summarise complex negotiations, analyse geopolitical trends from unstructured data, and even assist in drafting diplomatic reports.

- Proximity: AI is introducing a new form of cognitive proximity between humans and machines, with AI providing information processing and initial analysis freeing diplomats to focus on strategy, persuasion, and the uniquely human art of negotiation.

THEMES: Impact of technology on geopolitics, topics, and tools for diplomacy

Technology does not impact diplomacy monolithically; its effects ripple across three distinct yet interdependent dimensions: the geopolitical context, the diplomatic agenda, and diplomatic practice.

The following table maps the three technological revolutions against the three dimensions of diplomatic impact. This analytical matrix guides the analysis of the co-evolution of diplomacy and technology in this book. It serves as an initial research hypothesis. After being deployed throughout historical eras, this analytical matrix is revisited in the book’s concluding section.

Table 1: Analytical matrix for an interplay between diplomacy and technology

| Geopolitical & societal context | Topics on diplomatic agenda | Tools of diplomacy | |

| Writing | Enabling centralised administration facilitated by writings and archives. | Formalisation of spoken agreements into written treaties and diplomatic communication. | The organisation of diplomacy through written correspondence and archives. |

| Electric revolution | Creation of global empires connected by submarine cables | Agreements on international standards for telegraphy and radio. | Instant communication between diplomats and headquarters. |

| Digital & AI revolution | Geopolitical relevance of data, semiconductors, satellites, and submarine cables. | Governance of the internet and AI. | Use of social media, video conferencing, and AI tools. |

The geopolitical and societal context for diplomacy

This dimension examines how technology redistributes power, creates new geopolitical winners and losers, and reshapes the fundamental map of international relations. Technological advantage often translates into geopolitical power.

For example, the invention of the printing press was an essential factor in fueling the Protestant Reformation, forming the modern nation states and initiating the Westphalian international system.

In the 19th century, Britain’s dominance over the global submarine telegraph cable network created a near-monopoly on international communication, providing its empire with an unparalleled strategic influence over global affairs.

Today, the geopolitical context is increasingly defined by the US-China rivalry, a competition fought over key technologies like AI, 5G networks, and semiconductor manufacturing.

New topics for negotiation on the diplomatic agenda

New technologies invariably create novel problems and frictions requiring negotiated solutions. New topics arise on the diplomatic agenda requiring international cooperation, establishing shared norms, and sometimes creating new treaties or international organisations to govern them.

The proliferation of the telegraph in the 19th century, for example, necessitated the creation of the International Telegraph Union in 1865 (the precursor to today’s ITU) to standardise protocols and manage interconnections.

The sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912, a disaster exacerbated by incompatible wireless systems, led directly to the 1912 Radiotelegraph Convention, which established SOS as the universal distress signal and mandated radio interoperability.

More recently, the global expansion of the internet prompted the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) in 2003–2005 to address the broader social and economic implications.

Today, AI is placing many complex new issues on the diplomatic agenda, from regulating lethal autonomous weapons and protecting knowledge to dealing with AI and digital divides.

New tools and methods in diplomatic practice

This dimension focuses on the how of diplomacy: the tools, methods, and practices that diplomats use in their daily work. One of the first and still key tools of diplomacy is writing. According to the Sumerian epic Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta (c. 27th century BCE), the very invention of writing is triggered by the necessity of envoys to correctly pass the message to foreign rulers, avoiding the fallibility of memorising long messages.

Millennia later, Gutenberg’s printing press altered diplomacy by changing how diplomatic knowledge is organised and preserved. In the period of 1626–1629, Richelieu established the first ministries of foreign affairs centred around archives, a key feature of preserving institutional memory to this day. Printing also paved the way for newspapers and public awareness of both distinct places, wars, and negotiations.

During the Cold War, public radio broadcasts by services like the BBC, Voice of America, and Radio Free Europe became a central tool of public diplomacy and ideological competition.

In the 21st century, the modern diplomat’s toolkit includes, among others, social media for public outreach and crisis communication, secure video conferencing for negotiations, and data analytics.

AI is becoming the next transformative tool, assisting with data analysis, drafting reports, and providing real-time support during negotiations, thereby augmenting the capabilities of the human diplomat.

Table 2: Methodologies used in this book’s interdisciplinary approach

| Methodology | Focus | Relevance to diplomacy and technology |

| Annales school of historiography | Structure of historical time | Provides temporal layers (longue durée, etc.) |

| Socio-technical systems theory | Co-evolution of technology and society | Supports a co-evolutionary perspective |

| Actor-network theory | Networks of human and non-human actors | Analyses technology-diplomacy interactions |

| History of technology | Technological impacts on society | Provides case studies for specific technologies |

| Diplomatic history | Evolution of diplomatic practices | Outlines the main diplomatic events and treaties |

| Diplomatic theory | Diplomatic organisation and functioning | Supports analysis of technologies and diplomatic functions |

| World-systems theory | Global economic structures | Provides context for geopolitical analysis |

Many trajectories in the evolution of diplomacy and technology

Diplomacy and technology have many diverse origins, challenging the prevailing, often Eurocentric, narrative of reducing diplomatic history to important conferences and events of the last few centuries of modernity. The book shows that no single civilisation or culture ‘invented’ diplomacy or critical technologies.

Rather, diplomacy is a universal human practice that has emerged and evolved in parallel across diverse cultures and continents, wherever communities have engaged in sustained interaction.

The study moves beyond a Westphalian narrative to explore the sophisticated diplomatic systems that flourished outside of Europe. In Ancient India, the Arthashastra provided a detailed treatise on statecraft, espionage, and interstate relations that predated Machiavelli by millennia.

Imperial China developed a unique and enduring tributary system, a hierarchical model of diplomacy grounded in the pursuit of harmony and stable order, which managed relations with its vast periphery for centuries.

In the Americas, the Inca Empire engineered a high-speed communication network with its roads and chasqui runners, a system developed entirely independently of Old World models but serving the same function of administrative and diplomatic cohesion.

The book also recognises the diplomatic practices of African polities, fostering the trade and negotiation networks that sustained Afro-Eurasian linkages.

By adopting this comparative perspective, the book aims to expand the worldview by presenting a richer and more accurate tapestry of global diplomatic history. This approach underscores that while diplomacy’s tools and cultural expressions may differ, the fundamental challenges of communication, negotiation, and coexistence are universal and timeless.

Human and artificial intelligence in book research

This book is a product of the AI era it seeks to analyse. It is written by a human with the help of AI, a ‘desk researcher’, helping identify sources and flag redundancies.

The writing process is an illustration of the emerging human-machine work. The author provides the strategic direction, the historical and theoretical framework, the critical analysis, and the narrative synthesis that form the intellectual core of the work.

The AI augments the author’s research capabilities by efficiently managing and retrieving information from an extensive knowledge resource. The more AI was trained on authors’ books, blogs, and videos, the more it reflected the way of thinking and framing arguments.

For example, AI has helped activate more than 2000 pages of notes and reflections gathered by the author over the last three decades. The main lesson from this work is that AI is a very useful servant but a bad master.

By training and using AI, we also learn a lot about ourselves, our way of thinking and our biases.

Ultimately, this methodological approach brings the book’s central argument full circle. Just as this text was created by synthesising human insights and AI efficiency, the book argues that future diplomacy will thrive on similar interactions.

This book is an invitation to reflect on how the practices of diplomacy shaped through history can guide the effective use of today’s tools, ensuring that its core mission – to represent, engage, and seek common ground – continues to thrive in a rapidly evolving world.

A journey of an idea

The idea for this book developed over many years of research, teaching, and dialogue. Its foundations were laid during 2013 and 2014, when Diplo organised a series of advanced-level webinars on the evolution of diplomacy and technology, led by Jovan Kurbalija.

These sessions explored how major technological milestones – from early writing systems and the printing press to telegraphy and digital networks – influenced the tools and frameworks of diplomacy. Case studies from different civilisations and time periods illustrated these transformations, offering some of the first structured frameworks for understanding what would later be called digital diplomacy.

In 2021, this journey continued with the Masterclass series Diplomacy and Technology: A Historical Journey. Held monthly throughout the year, these sessions traced key moments in diplomatic history, from Mesopotamian scribes and Roman envoys to the rise of cyber diplomacy and artificial intelligence. They laid essential groundwork for what would become this book, expanding both the chronological scope and analytical depth of the original frameworks.

Finally, in December 2023, the first edition of History of Diplomacy and Technology: From Smoke Signals to Artificial Intelligence was published. Synthesising over two decades of research and teaching, the book offers a comprehensive narrative of how technological change has shaped the practice of diplomacy – from the earliest empires to the digital era.