There is a certain sepia-toned quality to our memory of ‘ping-pong diplomacy‘. In the spring of 1971, the story goes, a small delegation of American table tennis players, attending the World Championships in Nagoya, Japan, received a startling invitation: would they care to visit the People’s Republic of China? The ensuing trip was a spectacle of benign curiosity. There were handshakes, friendly matches, and tours of the Great Wall, all under the watchful gaze of Zhou Enlai. The entire affair possessed an almost amateurish charm, a diplomatic icebreaker accomplished not with the thunder of treaties but with the gentle, hollow pop of a celluloid ball. It was a time when the trivial act of playing a game together was seen as a profound political statement, a simple bridge across a vast ideological chasm. One finds oneself looking back on it now with a kind of wistful nostalgia, as one might look back on a childhood photograph, struck by the innocence of it all. The world that ping-pong diplomacy helped create has, in turn, transformed the very nature of sports diplomacy itself.

The celluloid olive branch

The logic of early sports diplomacy was rooted in the ideal of cultural exchange and understanding. The athlete was an unwitting ambassador, the sporting arena a neutral space where common humanity could, for a fleeting ninety minutes or a few frantic sets, transcend political enmity. The 1971 tour was powerful precisely because it was so unassuming. It was not a transactional deal; the Americans were not paid, and the Chinese were not seeking a specific concession. The goal was to thaw a relationship that had been frozen for two decades. It worked because, on the surface, the stakes were so low. Sport was the informal handshake that preceded the formal meeting, a gesture that cost little but signalled much. This was the model that persisted for years: a cricket match between India and Pakistan, a rugby tour of apartheid-era South Africa (albeit a deeply controversial one), and the Olympics as an ostensible festival of global unity. The power lay in the symbolism of participation itself.

The price of prestige

That quaint calculus has been comprehensively superseded by the brute force of capital. The modern iteration of sports diplomacy is less about cultural exchange and more about strategic investment, a field now dominated by a term that would have been alien to the ping-pong players of 1971: ‘sportswashing‘. Countries now view hosting mega-events like the FIFA World Cup or the Olympic Games not as a charming invitation to the world but as a multi-billion-pound exercise in nation-branding and the projection of soft power. The Qatar World Cup in 2022 and Saudi Arabia’s audacious investments in everything from its domestic football league to international golf are prime exhibits. The objective is no longer merely to open a door but to purchase a global reputation, to use the universal, apolitical appeal of sport to apply a glossy veneer over domestic political realities and human rights records. The athletic contest has become a commodity, a high-value asset in a state’s public relations portfolio, and its currency is influence.

The unwanted spotlight

This influx of state capital into sport has produced an inevitable and powerful counter-reaction. When a country spends lavishly to place itself at the centre of the world’s attention, it cannot control the direction of the gaze. The very act of hosting invites scrutiny that a more reclusive state might otherwise avoid. Consequently, the discourse surrounding major sporting events has become a de facto audit of the host nation’s values. We saw it with the protests over China’s human rights record ahead of the 2008 and 2022 Olympics, and it reached a fever pitch with the relentless focus on the rights of migrant workers in Qatar. The sports stadium is no longer just a venue for physical prowess; it is a courtroom for the court of public opinion. Journalists, activists, and fans now arrive not only with team colours but with a checklist of concerns, turning every press conference into a potential grilling on geopolitics. The sporting world, having accepted the state’s money, finds it can no longer credibly claim to be above the state’s politics.

A new voice in the game

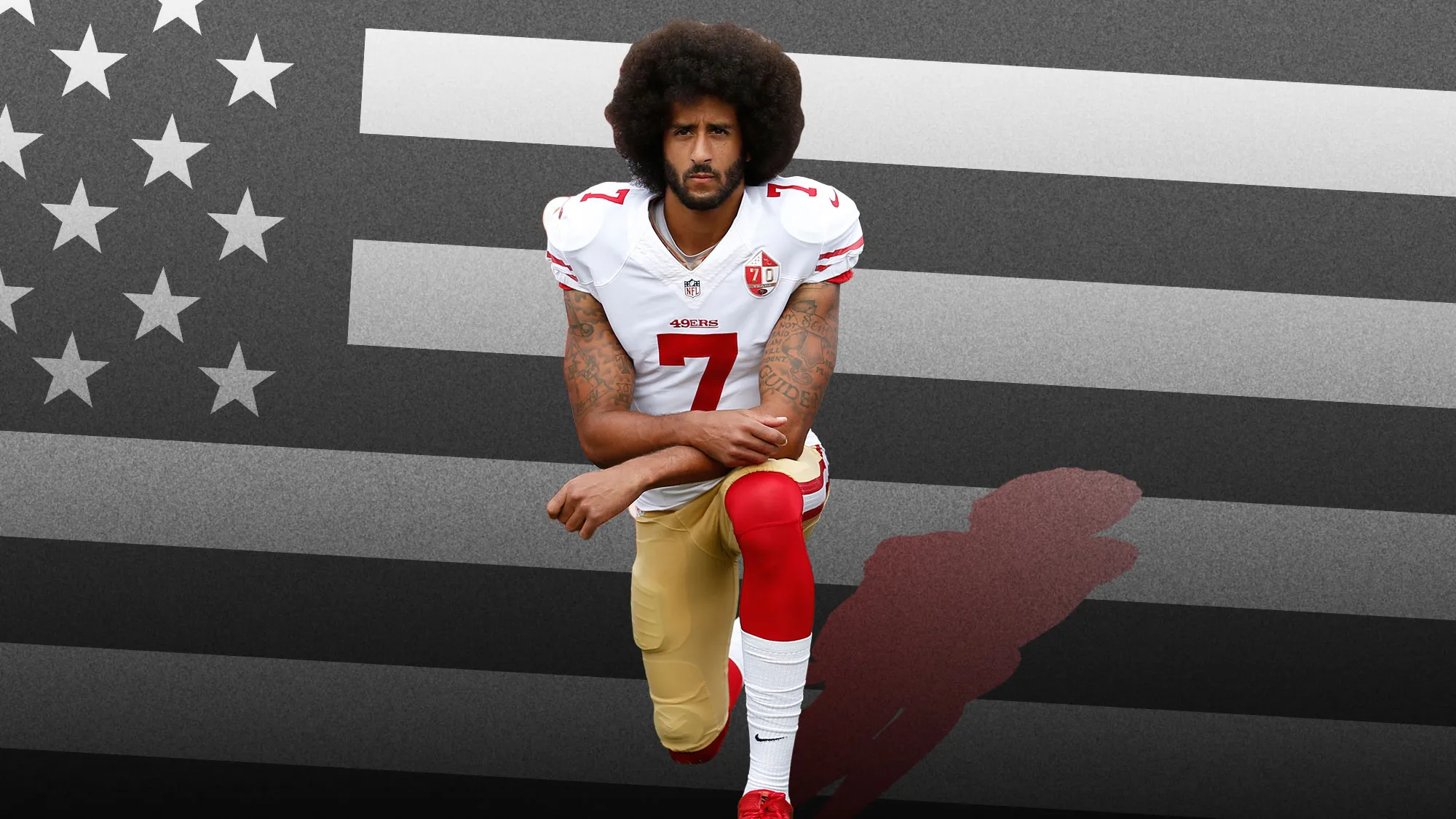

Perhaps the most intense shift has occurred not in the state ministries or corporate boardrooms, but on the pitch itself. The modern athlete is a global brand, a media entity with a direct line to millions of followers, and a progressively potent political actor. The old creed, famously attributed to Michael Jordan, ‘Republicans buy sneakers, too’, has been jettisoned by a new generation. From Colin Kaepernick kneeling to protest racial injustice in the United States to Marcus Rashford’s campaign against child food poverty in the UK, athletes are leveraging their platforms to force social and political conversations. They are no longer just pawns in a diplomatic game orchestrated by others; they are players in their own right. This individual activism complicates the state-led narrative, creating a new and unpredictable vector of influence. A government might wish for its national team to project an image of serene strength, only for its star player to tweet a message of dissent that reverberates across the globe.

The politics of the playing field

All these currents: money, human rights, and athlete activism are now converging on the most fundamental of questions – Who should even be allowed to play? The idea of boycotting or banning countries from international sport is not new, of course; the exclusion of South Africa during apartheid is the landmark case. But the practice has become a central and highly contested tool of modern statecraft. In the wake of the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Russian and Belarusian teams and athletes were barred from a wide range of competitions. Today, a similar and ferocious debate surrounds Israel. Citing the conflict in Gaza, a coalition of governments, activist groups, and sporting federations is demanding the exclusion of Israeli athletes and teams from global competitions, including the upcoming Olympics and FIFA-sanctioned events. The argument posits that participation in the international sporting community is not an inalienable right but a privilege contingent upon adherence to international norms. Whatever the outcome, the debate itself signifies the final, irrevocable collapse of the old ideal.

The journey from the ping-pong tables of Beijing to the fraught debates in the conference rooms of FIFA and the IOC is a story of lost innocence. Sport is no longer a gentle prelude to diplomacy; it is a chaotic, high-stakes, and deeply politicised arena where the contest for influence is as fierce as any match. The complex, heavy trajectory of global power politics has replaced the simple, hopeful flight of that little white ball. We may have lost the charming simplicity of the old game, but we have, perhaps, gained a more honest reflection of the world in which it is now played.

Click to show page navigation!