Most of us picture an ambassador’s residence as a quiet, formal place, full of polished furniture and history. The conversations there are careful and complex, centred on treaties and statecraft. But a strange thing is happening in our time: a new kind of diplomat is emerging. You’re more likely to find this person in a repurposed warehouse in London or a glass-fronted conference room in Palo Alto than on a traditional embassy row. They don’t talk about trade tariffs; they talk about data security and API protocols. They don’t represent a country. They represent a city, engaging in a new form of city diplomacy.

The city-state, it seems, is back.

A new map of power

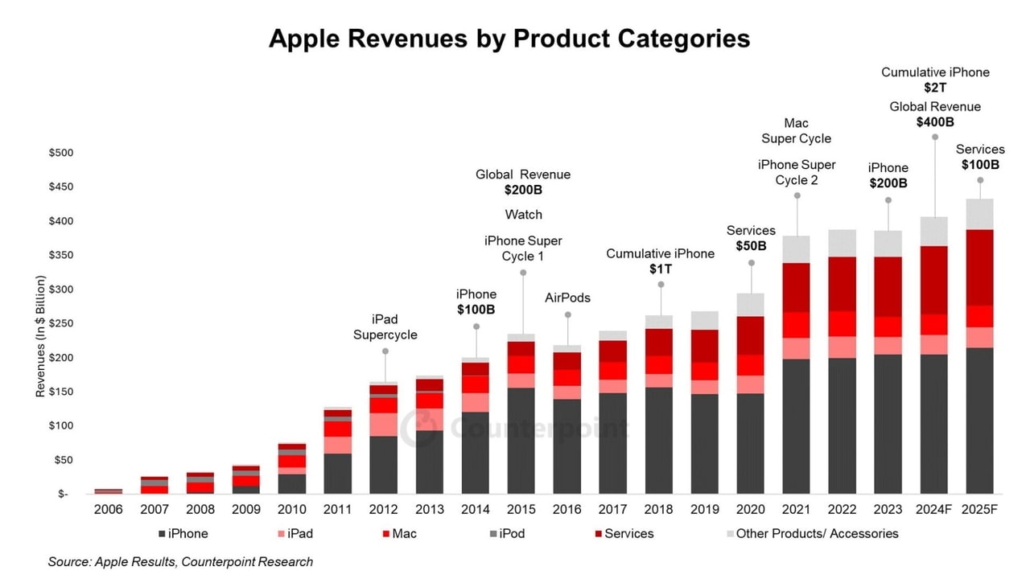

For centuries, the world has been organised around nation-states, a concept often traced back to the Westphalian system. This has been the bedrock of traditional diplomacy. Today, however, global power flows just as much between major cities and the tech giants that call them home. The scale is staggering: for instance, Apple’s 2024 revenue of over USD 380 billion surpasses the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of entire countries like Denmark and the Philippines. An algorithm designed in a Silicon Valley boardroom can affect the life of a person in Vienna more directly than a treaty signed in Geneva. This new situation requires a new kind of representative: the tech ambassador, a symbol of the city’s return as a major player on the world stage.

The new ambassadors

This is not just a ceremonial title. A growing network of over 50 cities worldwide, including pioneers like Amsterdam, Barcelona, and London, is creating these official roles to operate in a world where their economies are deeply connected to the global tech ecosystem. The biggest challenges modern cities face, from public transit and health to sustainable energy, all have technological solutions. A city can no longer afford to be a passive user of new technology; it has to actively negotiate its own terms.

So what does a tech ambassador actually do? The role is a mix of a diplomat, a venture capitalist, and a policy expert. One week, they might be in Seoul, building a partnership with a robotics firm. Next, they could be at a conference in Lisbon, promoting their city and sharing its vision for a more human-centred digital future.

Their job has two main parts. Outwardly, they are advocates, working to attract talent and investment. Inwardly, they are translators and guardians, helping their local governments create innovative policies that harness the benefits of technology while mitigating its risks. When a global company like Uber wants to operate on a city’s streets, this new diplomat helps set the rules, negotiating not over land, but over data sharing and workers’ rights, a practice often called TechPlomacy.

The hidden dangers

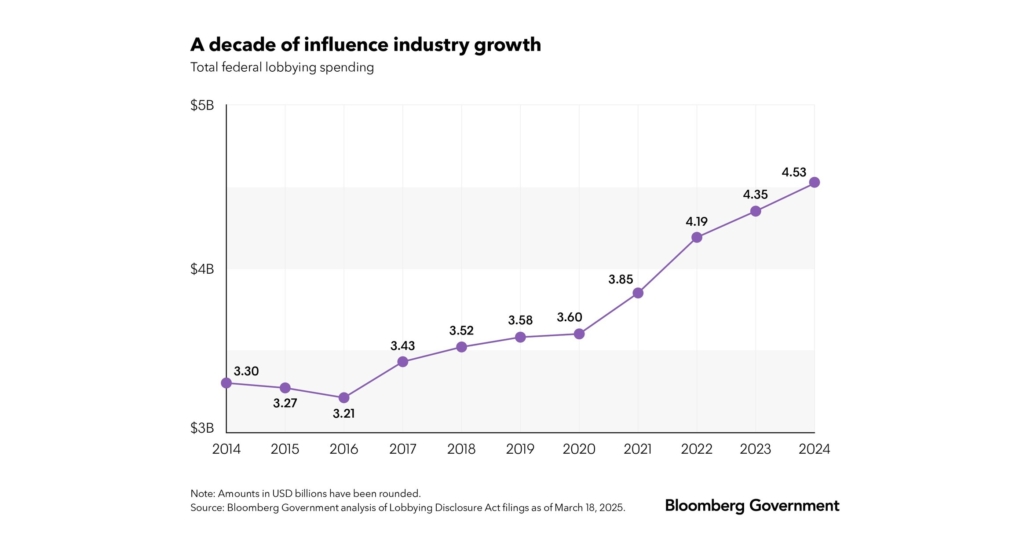

While the rise of the tech ambassador is a fascinating development, it is also full of serious risks. At the heart of the issue is a major power imbalance. This is clear from lobbying data: in 2024, the top five tech firms spent a combined USD 70 million on federal lobbying in the US alone, a sum that dwarfs the entire policy-making budget of many municipalities. Eager for the jobs and prestige the company brings, cities can end up agreeing to bad deals on everything from taxes to data governance.

There’s also the tempting idea of ‘technological solutionism’ – the belief that every complex urban problem can be solved with the right app or algorithm. This mindset can push aside other important solutions and limit a city’s imagination to only what is profitable.

The task ahead

Even more troubling is the potential for a loss of democratic oversight. When essential public services are run by private, proprietary algorithms, accountability can vanish. For example, some predictive policing algorithms have been shown to reinforce existing biases, with one independent audit finding that a model used in Chicago was unable to identify anyone who would be involved in a shooting.

The job of a traditional diplomat was to manage relationships between nations. The job of their modern, urban counterpart is to manage the complex relationship between technology and the city, the citizen and the corporation. As cities build these new alliances, they are creating a new kind of global influence. But the world they are building, made of data as much as it is of brick and mortar, requires not just a new kind of digital diplomacy, but our serious and constant attention.

Click to show page navigation!