One evening, as the world settles, a quiet ritual is playing out. On sofas in Santiago, in flats in Florence, in condominiums in New York, a decision is made. It is a small, private act, this business of scrolling through a seemingly bottomless digital library of film and television. And yet, it is quite possibly one of the more interesting geopolitical phenomena of our time. We are talking, of course, about Netflix. The company that, if you recall, got its start posting DVDs in little red envelopes has, almost by accident, become one of the most powerful purveyors of soft power on the planet. A digital diplomat who has an impact that traditional foreign ministries are only starting to understand.

A quiet click, a global shift

It turns out that a set of instructions, or an algorithm, can be an unexpectedly successful way to communicate or deliver messages. It’s an empire built, strangely enough, on that algorithm. The mysterious forces behind what we watch know us very well. They don’t just try to figure out if we’d enjoy a dark crime drama from Scandinavia or a lighthearted baking show from Britain. Instead, they have the power to turn a small, local show into a worldwide hit. Consider the improbable ascent of Squid Game. A year before its release, a hyper-violent, allegorical drama from South Korea was hardly anyone’s idea of a sure-fire global hit. But the algorithm, sensing a spark, fanned it into a wildfire. The show did more than entertain; it launched a thousand dinner-party conversations about debt, inequality, and the desperation of late-stage capitalism. The initiative showcased South Korea as a vibrant and exciting centre of bold and top-notch creativity. No cultural exchange or carefully arranged diplomatic visit could create such a strong, immediate effect.

Redrawn by subtitles

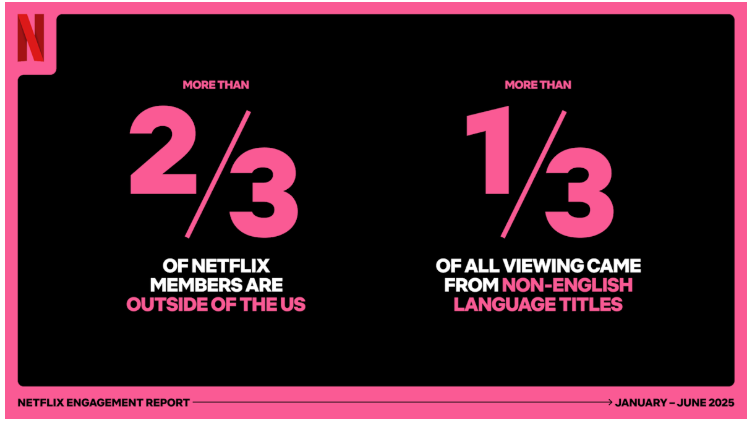

What Squid Game demonstrated was a fundamental rewiring of cultural currents. For the better part of a century, the flow of culture was a one-way street, a torrent of American-made content inundating the globe. Hollywood was the world’s storyteller. Netflix, however, began to systematically re-plumb the whole apparatus. By commissioning and promoting content from around the world, it turned a monologue into a sprawling, sometimes chaotic, global conversation. All at once, a Spanish heist thriller (Money Heist), a German time-travel puzzle (Dark), or a French caper about a gentleman thief (Lupin) could enthral viewers from Tel Aviv to Tokyo. This isn’t the stiff, state-sanctioned cultural diplomacy of old. It’s something far more subtle and, arguably, more powerful: the casual absorption of different languages, social norms, and histories, all consumed from the comfort of one’s living room. The world, it seems, is being redrawn not by treaties but by subtitles.

The fictions that fuel friction

Of course, this newfound power is not without its diplomatic headaches. When a platform’s remit is simply to entertain, it can find itself blundering into fiercely contested political territory. A historical drama is never just a historical drama, not when it involves living and very powerful people. Netflix’s The Crown, with its lavish and occasionally fanciful depiction of the British monarchy, has been a source of perennial anxiety for Buckingham Palace and, by extension, a British government periodically prompted to remind everyone that the series is, in fact, fiction. Elsewhere, the dynamic is less about royal sensibilities and more about raw national narratives, as documentaries that challenge official histories draw formal protests from governments that find their carefully curated stories being overwritten by a streaming service. Entertainment has become hopelessly entangled with statecraft, and television producers now wield a peculiar sort of influence once reserved for ambassadors and foreign correspondents.

Nation-branding by stealth

This points to a larger phenomenon, which some have called the ‘Netflix effect’, where a single show, amplified by the platform’s global reach, has the power to significantly impact culture, tourism, and consumer trends. It’s also a powerful idea recasting national identities in the collective global imagination. It’s more than just a surge in tourism to the picturesque filming locations of a popular show, though that certainly happens. It’s about the very branding of a nation. Spain, through shows like Money Heist and Elite, is cast as sleek, passionate, and modern. The popular image of Scandinavia has been irrevocably coloured by the moody, intelligent crime dramas that have become its signature export. This is nation-branding by stealth. For countries seeking to project a certain image on the world stage, of innovation, of openness, of creative verve, a hit Netflix show can be a more effective tool than a dozen trade missions. The catch, of course, is that this branding happens entirely outside of a government’s control. A national story is being hammered out in a writer’s room in Los Angeles or a production studio in Madrid.

Statecraft in the streaming age

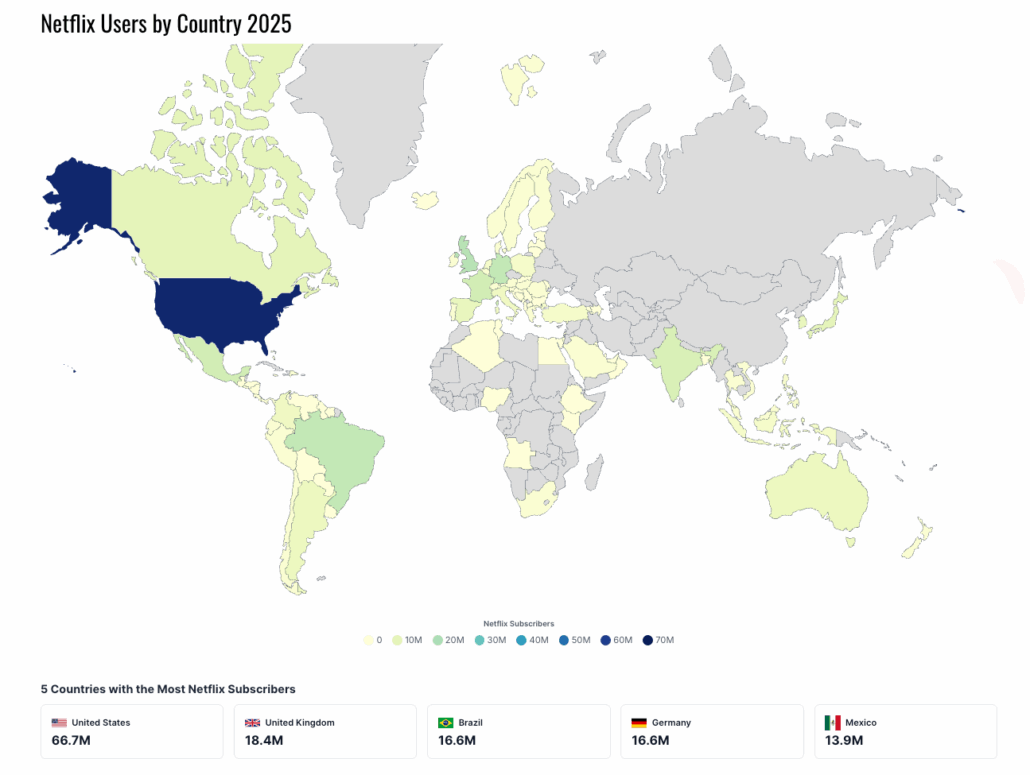

So, where does this leave the old art of diplomacy? Nobody is suggesting that foreign policy will soon be outsourced to Netflix executives, or that international summits will be replaced by season premieres. However, it would be unwise to overlook the significant changes that are happening. The old levers of power: military might, economic strength, and formal alliances, are now mixed in with a huge, chaotic world of digital culture.

Countries are learning that their story is no longer theirs alone to tell. It is being told, retold, and remixed on screens across the globe, every single night. The relationship between the state and visual media has deepened; the subtle click of a remote control in a dimly lit room now resonates, albeit subtly, within the corridors where critical decisions regarding national policies are made.

Click to show page navigation!