Hydrogen in shades of green

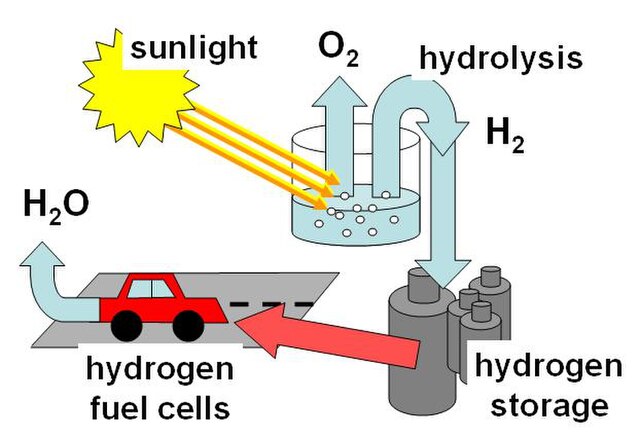

Hydrogen is an energy source that generates both immense optimism and significant challenges. Its basic idea is elegant. Fresh water is split into hydrogen and oxygen with electricity from renewable sources like wind and solar. The subsequent product is hydrogen, known as being ‘green’. We turn excess wind and sun into hydrogen molecules, which we can store, transfer, and later use in industry, for transport, heating, or electricity generation. Green hydrogen offers a decarbonisation pathway for steel, the car industry, and logistics.

While hydrogen may be the universe’s most common element, its story gets complicated here on Earth. You’ve probably heard hydrogen described with different colours: white, brown, grey, blue, and green. It’s crucial to know that these aren’t types of hydrogen. A molecule is a molecule with the same chemical characteristics. Instead, the colour is a label for its environmental footprint, revealing how it was produced.

Although hydrogen is a clean molecule, in most of its production it is extracted from fossil fuels in a process responsible for hundreds of tons of carbon dioxide every year. The only variant that genuinely lives up to the clean energy hype is green hydrogen, produced by splitting water using electricity from renewable sources like wind and solar, resulting in zero carbon emissions. This attribute makes hydrogen a basis for the worldwide effort to combat climate change. By offering a clean fuel whose production doesn’t pollute our atmosphere, green hydrogen aligns perfectly with the world’s urgent mission to decarbonise our economy and clean the air we breathe. Hydrogen’s production is a conversion process, not an extraction, so it can happen almost anywhere.

When it comes to energy, hydrogen has the highest energy density per mass, but low ambient temperature density results in low energy per unit volume. Hydrogen can be stored in the form of a gas or a liquid. Still, liquid storage requires cryogenic temperatures since this element boils at -252.8 °C. An impressive energy density provides approximately 120 MJ per kilogram, nearly three times that of gasoline’s 44 MJ per kilogram. In terms of volume, it is at a disadvantage. Even liquid hydrogen has a much lower volumetric energy density than gasoline, which results in extensive and costly storage tanks. This is an excellent example of how physics can transform apparent advantages into engineering challenges.

It is important to mention a few facts. Today, producing green hydrogen costs around one and a half to six times more than fossil-based production. China is a leading country in this technology. As the largest global producer of green hydrogen and the manufacturing capacity of electrolyser plants reached 25 GW per year, China accounts for 60% of the world’s share. Ultimately, the potential for green hydrogen is not evenly distributed. The most significant potential lies in the sun-drenched and wind-swept regions of Africa, the Americas, the Middle East, and Oceania. About 40% of green hydrogen production projects are located in arid areas, combining desalination and wastewater technology utilisation.

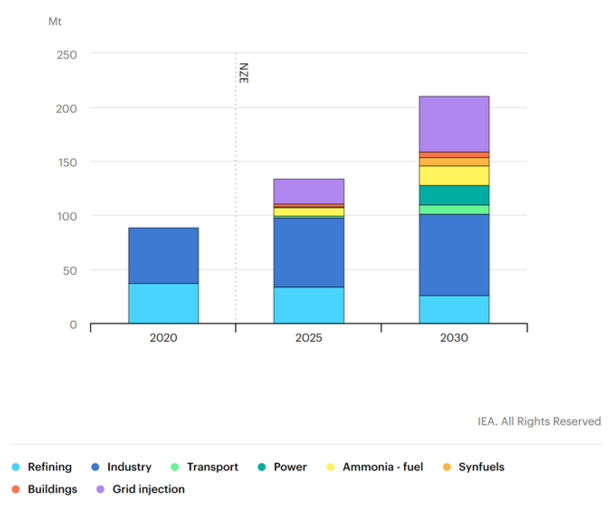

According to the Hydrogen Council, low-emission hydrogen could supply up to a fifth of global energy needs and generate a market worth USD 2.5 trillion by 2050. The final shape of our hydrogen future, however, will be determined by a diplomatic race, not just for resources. This is where geopolitics comes into play.

The geopolitics of energy transition

While the vision for green hydrogen is powerful, the sector currently faces several significant challenges. The first among them is price. The production of green hydrogen remains far too expensive compared to grey or blue, which is attributed to the high cost of electrolysers.

Second, this is an energy-intensive process. Hydrogen faces a particular problem that lies in its natural properties. It isn’t easy to store or transport, and it has an extremely low density compared to other fuels.

Third, our energy infrastructure network was built for fossil fuels, from pipelines to fuelling stations. Retrofitting this network for hydrogen is a massive engineering task, which often urges complete replacement and a considerable capital investment.

Finally, the market for green hydrogen is still nascent, and a clear regulatory framework is essential to ensure the safety of investors in funding this emerging industry. Despite these challenges, momentum for green hydrogen is increasing.

It’s not a simple fuel swap, but a fundamental transformation from politics and technology to the environment and economy. By 2050, clean hydrogen could meet a remarkable 12% of global energy demand, produced predominantly from renewables and supplemented by natural gas paired with carbon capture. Although the price of renewables is decreasing, the expense of hydrogen transport remains high. That is why countries seek regional energy partnerships, forming new geopolitical alliances. Such a situation would lead to increased market competition, making it difficult for any country to dominate.

Countries blessed with abundant sun and wind are poised to become the new energy exporters, wielding fresh geopolitical and geo-economic influence. We are already witnessing the birth of new trade routes and a wave of ‘hydrogen diplomacy’, with over thirty countries designing import and export strategies. This forming network encourages countries to diversify their energy portfolio from traditional energy partners. Even countries like the UAE and Saudi Arabia actively explore blue and green pathways.

From politics to pipelines, the European Union is steadily paving the way for green hydrogen. The EU is putting together a massive budget of EUR 1 trillion for the green transition during this decade. Although it is often mentioned that hydrogen will take half of that, it is still not an official number. The total fund consists of a complicated combination of government and private money, and different elements will influence the decision. However, the Hydrogen Strategy of the EU (2020), which is very ambitious and has specific 2030 targets, like 40 gigawatts of electrolysers. The REPowerEU Plan in 2022 further increased the significance of hydrogen by projecting its contribution to the EU’s total energy demand to around 10% by 2050, primarily through the decarbonisation of heavy industry and transport. In the same year, the European Commission came up with the idea of the European Hydrogen Bank. The primary aim of the bank is to promote investment and generate business opportunities around the production of renewable hydrogen, not only in Europe but also in the world. It should be noted that it is not a bank in the traditional sense. Instead, it is a financial mechanism run by the Commission’s own services.

On the other hand, China, as the largest producer and consumer of hydrogen, is not idle. This country presented the goals of hydrogen spanning medium to long term, which include 50,000 hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles being deployed, and the production of green hydrogen being set at 100 to 200 kilotonnes per year. The hydrogen refuelling stations have been built as part of the plan, and this fuel has been integrated into the key industrial sectors.

Japan has pledged to support the radical idea of a ‘hydrogen society’, a future with extensive hydrogen energy in all areas of its economy. The plan includes everything from vehicles and steel manufacturing to providing gas for homes and electricity production. Australia also dreams of becoming a world leader in hydrogen production.

So, where is the geopolitics?

Due to its abundant solar irradiation and good wind conditions, the Middle East has among the cheapest renewable energy sources in the world. Countries like Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Qatar are redefining their long-term energy strategies and positioning themselves as future vital players in the green hydrogen ecosystem. Saudi Arabia is currently building the world’s largest green hydrogen project. A joint venture between ACWA Power, Air Products, and Neom, the massive facility will be capable of producing over 200 kilotonnes of green hydrogen per year if it operates every day. For context, the largest existing green-hydrogen facility, in China’s Xinjiang region, has a capacity of just over 44 kilotonnes per year.

European partners, such as Siemens Energy and Lufthansa, have already launched significant hydrogen projects in the Middle East. Namibia also leverages its vast potential for solar and wind power to build a competitive green hydrogen industry. The country’s strategy is not only to boost its own energy supply and create jobs but also to become a key exporter of green hydrogen, with a particular focus on markets like Germany.

To help realise this vision, a dedicated hydrogen partnership between Namibia and Germany is facilitating a crucial exchange of knowledge and technology. This collaboration is designed to accelerate the development of a full-fledged clean energy and hydrogen industry, fostering the creation of sustainable value chains within Namibia. The energy ministries of Italy, Germany, and Austria have signed an agreement to work together to develop a hydrogen transport network from the southern Mediterranean to northern Europe. The connection known as SoutH2 was granted priority status from the European Commission.

Africa and the Middle East are not the only critical geo-economic hubs for the production of green hydrogen. Kazakhstan possesses significant potential for solar and wind energy, which positions the country to become a major producer of green hydrogen. This represents a strategic opportunity for the government in Astana to diversify its domestic energy mix and create a new, clean export commodity for international markets. The country’s hydrogen strategy is notably versatile.

While green hydrogen is the long-term goal, Kazakhstan is also well-placed to develop blue hydrogen. This is due to its vast natural gas reserves and potential CO2 storage sites, which, combined with carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology, can provide a medium-term pathway to scale up hydrogen production. A landmark initiative in this area is the Hyrasia One project, a massive USD 40-50 billion venture agreed upon with the Svevind Energy Group in October 2022. The project aims to build a 40 GW renewable power station in the Mangistau region to produce two million tons of green hydrogen annually by 2030. The output is intended for domestic heavy industry and export to Europe. The project is strategically planned to connect to the EU-backed Green Energy Corridor, enhancing its geopolitical significance.

By unlocking hydrogen imports from North Africa and Kazakhstan, Europe aims to move away from Russian gas as an energy carrier for the steel, chemical, and refinery industries. Whoever exports hydrogen to the EU must prove its ‘green’ origin. Raising the barrier for export to the EU makes placing grey and blue hydrogen more difficult, and strategic partnerships with countries like Namibia and Kazakhstan are essential. Apart from the goal of distancing itself from Russian gas, the EU wants to impose itself as an economic competitor to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Hydrogen diplomacy aims to secure partners for hydrogen production and export in suitable geographical areas. The new branch of diplomacy will only gain importance, and the EU will lead the way in practising a new skill.

Producing green hydrogen is currently more expensive than producing grey hydrogen from natural gas by reforming methane. Green hydrogen is not a ‘silver bullet’ but is vital to the overall decarbonisation strategy. Whether it will remain just a good idea or a commercial energy source depends primarily on the price of electricity from renewables.

For this reason, regions illuminated by the sun’s rays and areas where the winds constantly blow are crucial for future development. However, the ability to produce green hydrogen at any location will prevent the formation of an oligopoly like the one in oil and gas production. In 50 years, hydrogen will become a significant and unavoidable part of our daily lives. To be genuinely committed to decarbonisation, we must include green hydrogen in our energy mix.

Consequently, we must include green hydrogen as a variable in geopolitical calculations.

Click to show page navigation!