Long before fibre-optic cables crisscrossed the planet, a web of knotted cords and mountain runners kept an empire connected. In the high Andes, the Inca civilisation mastered the art of information and communication in ways that remain astonishingly relevant today.

For the Incas, diplomacy was inseparable from logistics and technology. To govern a vast and diverse empire stretching thousands of kilometres, from present-day Colombia to Chile, they needed both data and delivery. In other words, they needed the ancient equivalents of our databases and communication networks. Their solutions – the quipus and chasquis – formed one of history’s most remarkable systems of knowledge management.

Quipus: Data before the digital

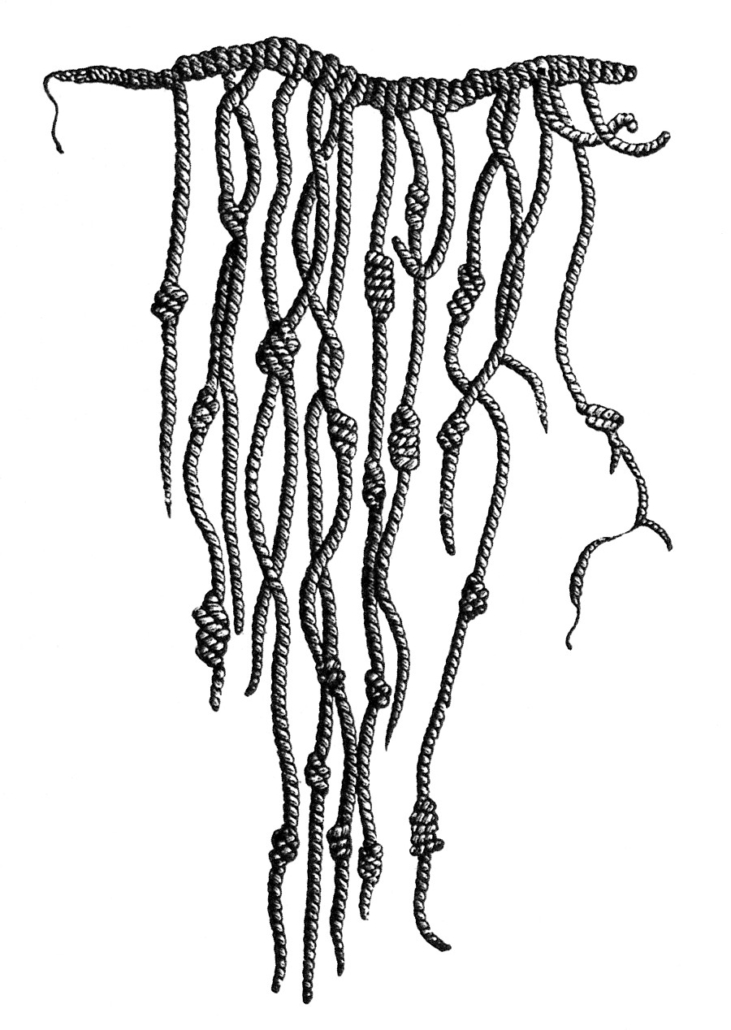

Imagine a world without writing, yet rich in data. The Incas recorded census information, tax obligations, inventories, and decrees using quipus, bundles of strings with carefully arranged knots, colours, and lengths. These were not primitive curiosities but sophisticated data-storage devices. Each knot pattern encoded numerical and possibly even narrative information.

In modern terms, the quipus was both database and algorithm – a physical interface between information and interpretation. Decoding it required trained specialists who understood the conventions of meaning, much as digital systems today depend on coders and analysts. The quipus made it possible to govern complexity without the written word, a feat that challenges many of our assumptions about literacy and record-keeping.

Chasquis: The human network

If quipus were the Inca data cloud, the chasquis were its delivery system. These elite messengers, running in relays along stone-paved roads that snaked through the Andes, carried quipus and oral messages from one post to another. Each chasqui covered short distances at great speed before handing off the message, an astonishingly efficient system capable of moving information hundreds of kilometres in a single day.

Think of it as the world’s most athletic API, powered by endurance, coordination, and trust. Every runner was both a node and a link in a resilient communication web. The system worked not through machines, but through humans – precisely synchronised, highly trained, and bound by purpose.

It reminds us that the infrastructure of diplomacy has always depended as much on people as on tools. Whether a chasqui sprinting through the mountains or a digital envoy navigating cyberspace, the human element remains indispensable.

Technology in the service of diplomacy

The Inca information network was not technology for technology’s sake. It served a clear diplomatic purpose: integration and governance. Communication enabled coordination, and coordination sustained cohesion across dozens of languages and cultures. The roads, the runners, and the cords were all instruments of stability, a means to manage diversity within unity.

There’s a lesson here for modern diplomacy. In every era, the challenge is not only to collect and transmit data but to do so in a way that sustains trust and coherence. The Incas achieved this through precision, ritual, and human connection – values that our algorithmic systems often overlook.

Today’s diplomats navigate encrypted cables and data dashboards instead of knots and cords, but the essence of the task remains the same: how to move information reliably, how to interpret it wisely, and how to use it to build and sustain relationships.The quipus and chasquis remind us that technology is never just technical. It is cultural, political, and profoundly human.

Further reading

For more stories on how communication technologies have shaped diplomacy – from the quipu to the quantum computer – consult the 2nd edition of History of Diplomacy and Technology.

Click to show page navigation!