There was a moment, in the early part of 2024, that spoke volumes about the peculiar state of modern power. As the nations of the European Union readied themselves for parliamentary elections, Margaritis Schinas, Vice President of the European Commission, did something that would have been unimaginable to the striped-pants diplomats of a generation ago. He publicly appealed to an American. Not to the President, nor to the Secretary of State, but to Taylor Swift. Schinas expressed his hope that the pop superstar, then on the European leg of a world tour of staggering proportions, might use her considerable platform to nudge young Europeans toward the ballot box. It was not, he insisted, a joke. It was a sober admission of a new geopolitical reality, one underscored by the fact that a single Instagram post from Swift had recently driven a surge in voter registration back in the United States.

The incident, brief as it was, illustrated a significant change in international affairs: the rise of celebrities as a powerful and often independent political force. Their influence is something that traditional institutions of the state both seek to gain and struggle to control fully. This phenomenon, which scholars have christened ‘celebrity diplomacy’, has journeyed from the quirky periphery of global politics to its very centre. It is a complex entanglement of media, culture, and statecraft that erodes the old conviction that diplomacy is the exclusive province of governments and their accredited emissaries. It demands to be taken seriously.

Celebrity diplomacy, it turns out, has evolved from a state-approved tool for raising public awareness – think of a film star politely cutting a ribbon – into something far more multifaceted and independent. In our hyper-mediated age, it offers startling opportunities to set global agendas. Still, it also brings significant risks, raising complex questions about accountability, legitimacy, and unintended consequences. To understand this force, we must trace its intellectual origins, follow its historical arc, and critically examine its curious role today.

From foggy bottom to the red carpet

The intellectual scaffolding for all of this was built, perhaps unwittingly, by the political scientist Joseph Nye. It was Nye who gave us the now-ubiquitous concept of ‘soft power‘. Unlike ‘hard power’, the blunt instruments of military coercion or economic inducement, soft power is the subtler art of getting what you want through attraction and persuasion. A country’s soft power, Nye argued, flows from three sources: its culture, when others find it appealing; its political values, when it lives up to them; and its foreign policies, when they are seen as legitimate.

Celebrity diplomacy is a form of soft power made flesh. Celebrities are, after all, cultural products themselves, and they can serve as charismatic conduits for the very values a nation hopes to project. When a globally famous actor speaks out on a cause, she is wielding a form of influence rooted not in command but in cultural allure. This places the practice within a constellation of related arts. It is a form of public diplomacy, reaching over the heads of governments to engage directly with foreign populations. It is a cousin to cultural diplomacy, which uses the exchange of art and ideas to build bridges. But most profoundly, it is a prime specimen of citizen diplomacy, the great modern trend of non-state actors wading into the stream of international relations.

It was the scholar Andrew F. Cooper who gave the phenomenon its name and its first rigorous analysis. Celebrities, Cooper argued, have become an ‘alternative form of agency’ in world politics, occupying a space of public trust that traditional politicians have often vacated. He coined a memorable term for the process at its most potent: the ‘Bonoization’ of diplomacy. He was referring, of course, to the U2 frontman, who managed to take an impossibly complex and unglamorous issue, third-world debt relief, and place it squarely on the G8 agenda. This was something new. Bono wasn’t just raising awareness; he was getting unprecedented face time with world leaders, framing arcane financial problems in morally urgent terms, and actively shaping policy. He had become, in Cooper’s words, an ‘ideational figure who frames and sells ideas within the international community’.

Here, a crucial distinction must be made. The terms ‘humanitarianism’, ‘activism’, and ‘diplomacy’ are often jumbled together, but they describe different rungs on a ladder of engagement. Celebrity humanitarianism is about alleviating suffering, often through charity concerts and telethons that pull at the heartstrings. Celebrity activism is about advocating for change, sometimes in direct opposition to state policy. But celebrity diplomacy, in its purest form, requires a leap into the official world. A celebrity crosses the threshold from activist to diplomat at the precise moment they are ‘accredited as having standing and legitimacy by the counterparts to whom they seek to negotiate’. Their power is no longer just their own; it is co-created, legitimised by the very state or international body they seek to influence. It is the move from the protest line to the negotiating table.

The evolution of the celebrity ambassador movement

The practice has a surprisingly long pedigree. The United Nations, in a moment of inspired public relations, formalised it in 1953 by appointing the actor Danny Kaye as the first Goodwill Ambassador for UNICEF. In those early days, the role was simple: lend a famous face to a good cause, raise some funds, and generate positive press. It was a quiet, largely uncontroversial affair.

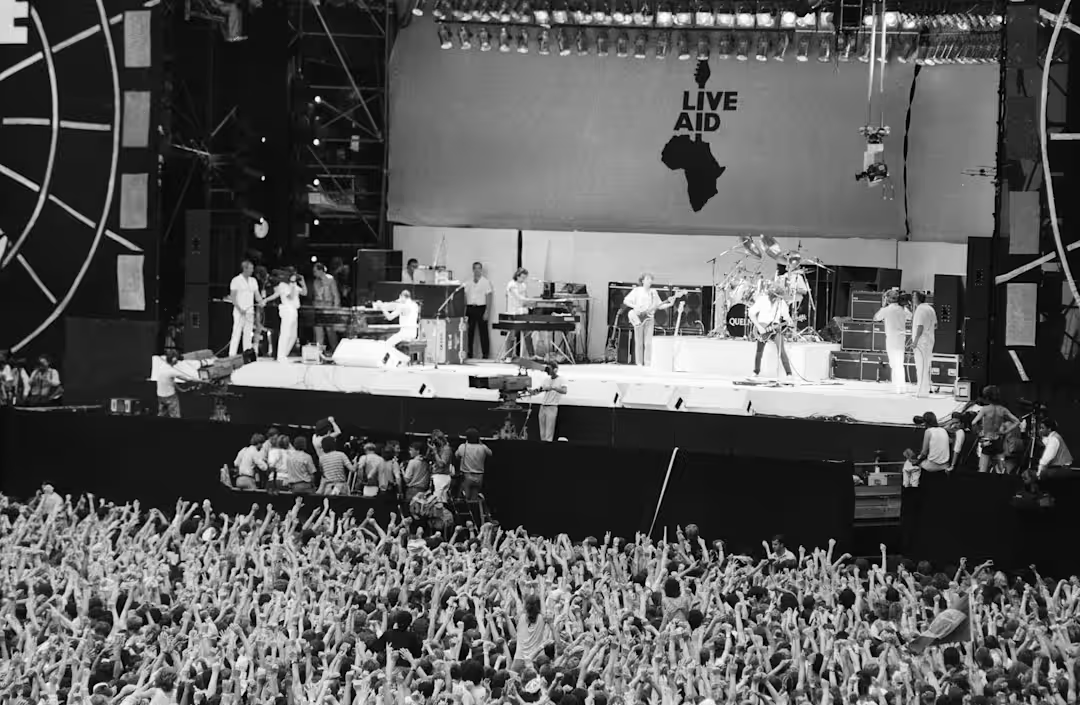

Then came the nineteen-eighties. The dawn of 24-hour global news and the rise of MTV created a media ecosystem in which a celebrity cause could catch fire globally. Live Aid, in 1985, was the watershed moment. Organised by the musicians Bob Geldof and Midge Ure, it was a media spectacle of staggering scale, demonstrating that celebrity power could mobilise mass audiences and rivet the world’s attention on issues like famine.

The evolution from that model to the present day is perfectly captured in the contrast between two of the UN’s most famous envoys: Audrey Hepburn and Angelina Jolie. Hepburn, a UNICEF ambassador from 1988 until her death, embodied the classic approach. She undertook the work largely after her film career had wound down, focusing on the welfare of children in a heartfelt and deeply compassionate manner, but was rarely overtly political.

Jolie represents the modern, professionalised iteration. For over two decades with the UN Refugee Agency, first as a Goodwill Ambassador and later as a Special Envoy, she has maintained a blockbuster acting career while immersing herself in the grimmest realities of international conflict. She hasn’t just visited refugee camps; she has entered active war zones. Her advocacy has moved beyond general humanitarianism to tackle deeply political and complex security matters, most notably the campaign to end the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war. The shift from the Hepburn model to the Jolie model is a symptom of a changing world, one where the lines between entertainment, advocacy, and statecraft have irrevocably blurred.

A toolkit of influence, and its discontents

Today, the celebrity diplomat operates with a sophisticated set of tools. They are agenda-setters, cutting through the media cacophony to elevate neglected issues. They are persuaders, framing complex problems in emotionally resonant terms. And they are mobilizers, translating their immense ‘celebrity capital into political capital’ by speaking directly to their legions of followers. The ways this toolkit is used, however, vary wildly, revealing the inherent tensions of the craft.

South Korea has executed a masterclass in state-sponsored soft power. The global phenomenon of K-pop has been harnessed as an explicit tool of foreign policy. The supergroup BTS isn’t just making music; they are delivering speeches at the UN and meeting with American presidents at the White House. These are not personal passion projects; they are carefully calibrated diplomatic manoeuvres designed to project an image of a modern, dynamic Korea.

At the other end of the spectrum lies a cautionary fable from 2012, when the reality-television star Kim Kardashian visited the Kingdom of Bahrain. At the very moment the Bahraini regime was suppressing pro-democracy protests, Kardashian, then boasting over thirty-two million Twitter followers, posted effusive messages like: ‘I’m in love with the Kingdom of Bahrain’. As the analyst Mark Lynch observed, her posts generated positive publicity for a Bahraini regime which carried out an unspeakably brutal crackdown. It was a stark lesson in unintended public diplomacy, where a massive platform, combined with a vacuum of political context, can inadvertently provide diplomatic cover for authoritarianism.

This points to the fundamental struggle now defining the field. It is a tug-of-war between states trying to instrumentalise celebrity for strategic ends (the South Korean or, in a more coercive vein, the Chinese model, where stars are effectively indentured to the Communist Party) and the rise of autonomous celebrity superpowers who operate outside of state control. Taylor Swift is the apotheosis of this latter model. Her influence is personal, not national. That a European Commission vice president would openly wish for her intervention reveals the new power dynamic: the state is no longer the puppet master but a supplicant, hoping to catch some of the light from an independent star it cannot control.

A crisis of legitimacy

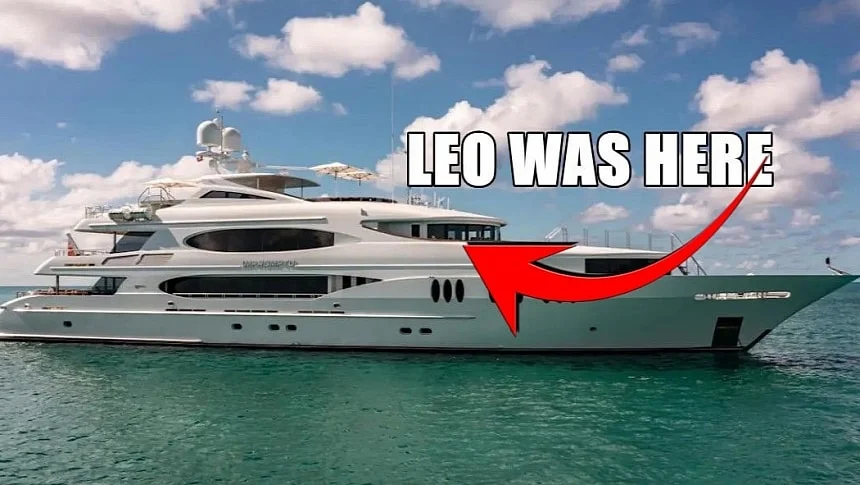

For all its prominence, celebrity diplomacy is riddled with critiques. The most damning is the ‘democratic deficit’. These are unelected figures displaying real political power, their access to the corridors of power granted by the arbitrary currency of fame, not a popular mandate. Cynicism about their motives is rampant, with their activism often viewed as little more than sophisticated brand management. When an environmental crusader like Leonardo DiCaprio is photographed on a carbon-belching superyacht, it not only invites charges of hypocrisy but can lead to ‘soft disempowerment’, damaging the very cause he champions.

There is also the persistent critique of a Western-dominated stage, where famous actors from Europe and North America risk reinforcing the hoary trope of the ‘white saviour’, swooping in to rescue a passive Global South. This dynamic can obscure the work of local actors and misrepresent complex political failures as simple humanitarian crises solvable by Western charm and charity.

Even the UN, the institution that started it all, appears to be struggling. A study by the USC Centre on Public Diplomacy found the UN’s celebrity programs to be marked by ‘programmatic incoherence’, poor branding, and a frustrating pattern of media attention that flares up at the moment of a celebrity’s appointment and then dies out, doing little to advance long-term policy goals. The brutal truth may be that while celebrities are peerless at attracting attention to themselves, the challenge of converting that fleeting attention into sustained, effective, and democratically legitimate policy change remains largely unsolved.

The future of fame in foreign policy will be more fragmented and contentious than ever. The heroic model of a single Bono or Jolie is being supplemented by the distributed power of ‘fan armies’, like the BTS fans who famously matched the band’s million-dollar donation to Black Lives Matter. Influence is becoming decentralised. Taylor Swift’s call for voter registration didn’t require a single meeting in a hushed office; it was a broadcast to millions, a shaping of the political weather from the ground up.

Celebrity diplomacy, then, is not going away. It is too deeply woven into our media culture, too valuable a tool in an age of distraction. But its character is changing. The future will be less about a few designated ambassadors and more about steering a chaotic ecosystem of influence. For the old guard of statecraft, the challenge is no longer whether to engage with this world. The far more challenging task is learning how to operate within a global public square that they can neither control nor afford to ignore. It will remain a powerful, but inherently volatile force in the affairs of the world.