NGOs and foreign policy evolution

I have recently seen the suggestion that, in the context of introducing good governance to foreign affairs, states should accept nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) as contributors to a national foreign policy. ‘Good governance’ is an emotionally loaded term used to outline a theoretical and uniform Platonic ‘best practice’, to which all countries and their ministries of foreign affairs should aspire.

Arguing against suggestions for ‘good practice’ is akin to challenging motherhood and apple pie. Of course, MFAs can become more effective if they become more inclusive (unless bureaucrats tie themselves up in knots managing inclusiveness). Rather than arguing the principle, therefore, I shall look at experience. In doing so, I shall define NGOs as ‘political pressure groups with a foreign relations attitude’, irrespective of their institutional structure. Such groups embody a bottom-up approach – the wishes of at least some of the governed.

In my broad definition, NGOs have a long history of involvement in foreign affairs. In China three thousand years ago, ‘the interplay of trade and expansion had been gradually pushing the northeastern frontier of China to as far as northern Korea’ (see Trade and Expansion in Han China: A Study in the Structure of Sino-Barbarian Economic Relations by Ying-Shin U). At that time, diplomats were traders, and traders were known to impersonate diplomats, for the diplomatic language bears witness to the fluidity of the border between public and private interest.

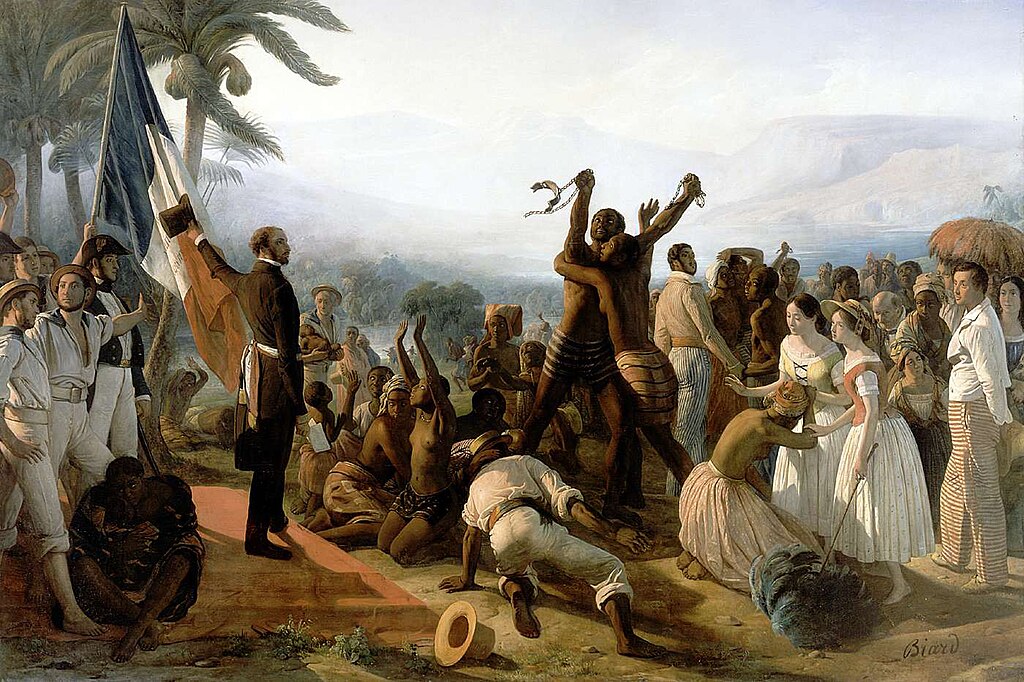

While the trade interest never receded, NGOs over time developed further ambitions. In the West, groups urged their governments to effect regime or cultural change abroad. Early on, religious groups pushed for jihad or crusades. Missionary and anti-slavery societies came next (see Power, Faith, and Fantasy: America in the Middle East 1776 to the Present by Michael B. Oren). As nationalism replaced religion as a collective ideal, groups began to advocate blessing the barbarians with democracy and universalistic human rights. Byron and his friends in Greece may have been precursors. Gladstone was in Naples in 1850/51 and publicly urged Great Britain to intervene on behalf of the opposition to the king (Gladstone visited Naples, witnessed the imprisonment of liberals, published letters condemning the government as ‘the negation of God erected into a system of government’, and later used this stance to build his political career). Western countries enforced consular protection at the mouth of the cannon (the case of Don Pacifico in Athens, whose home was vandalised in 1847, led Britain under Lord Palmerston to blockade Piraeus until compensation was paid, citing the principle of extraterritoriality – later echoed in USA refusals to submit soldiers to international tribunals).

British and Piedmontese Masonic Lodges may have funded part of Garibaldi’s mad dash from Sicily to Naples in 1860 (see Maledetti Savoia by Lorenzo Del Boca). As nationalism enfolded, irredentist groups at home urged action over the border. Colonial expansion was a popular ambition. The emergence of mass armies created NGOs devoted to preparing the citizenry to fight wars (in Germany, e.g. they were the Schützenvereine, with an enrolment of three million). These organisations were often a hotbed of jingoism. Arguably, an NGO – Serbia’s Black Hand – started WWI. One could contend that terrorist groups are ‘deviated’ NGOs.

Mass migration created diasporas. The electoral power of the German minorities in the USA delayed the country joining WWI. Irish immigrants in the USA sustained Irish independence (and beyond). Diasporas created and sustained states – Israel is a good example. Remittances kept China’s imperial government afloat in the second half of the 19th century. Nowadays, a diaspora’s political and financial clout can sway policies both in the host and in the origin country.

Domestic politics can create strange bedfellows. The USA yellow press, looking for better sales, pushed for the country’s intervention in Cuba in 1898 and then the Philippines (see The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst by David Nasaw). In 1913, Italian Prime Minister Giolitti ‘bribed’ the political right into conceding general male franchise by starting a colonial war in Libya.

Post-war expansion of NGO influence

The end of WWII brought about a surge in ‘do-goodism’ abroad. NGOs concerned themselves with economic development but also cultural themes (both Soviet and Western blocs secretly funded cultural NGOs in the 1950s to promote their civilisational models). They soon expanded into institutional development. From the Baltic to the Cape of Good Hope, volunteers taught democracy, human values, and free markets. NGOs vociferously and successfully called for military interventions (Africa, Libya, and now the Levant).

My cursory historical excursion shows that NGOs have been able to influence foreign policy. Particularly today, foreign policy as ‘elitist’ is diplomatic lore. NGOs will also affect foreign policy in the future. The problem, then, is not whether to give NGOs a voice. The core issue is what role their contribution should take.

Conviction, responsibility, and policy

Foreign policy, I would contend, is not the triangulation of private interests, but a careful balancing of private and public interest in foreign affairs. This is the core task of an MFA (not being ‘his master’s voice’ abroad). As input and enrichment of this process of acquiring knowledge and developing foreign policy, NGOs’ knowledge and arguments are welcome. There is a tendency today, unfortunately, to see government as default incompetent – an empty vessel best filled by the wisdom of particular interests (see Individualism and Economic Order by Friedrich Hayek; Thatcher and Reagan popularised this trend, though Reagan also stressed the ‘common good’ in foreign affairs). When in half an hour an individual can sway foreign policy – as was the case for France’s intervention in Libya (French philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy convinced Sarkozy to topple Qaddafi, lobbied Hillary Clinton for USA involvement, and later admitted his motives were as much symbolic as humanitarian) – this is downright reckless. It is evidence of the curse of O’Connor’s Law: conviction is inversely proportional to experience.

Conviction sways. Conviction sways money; money reinforces conviction. It is a self-reinforcing process. Conviction backgrounds experienced knowledge. In conviction is imminent danger.

The post was first published on DeepDep.

Explore more of Aldo Matteucci’s insights on the Ask Aldo chatbot.

Click to show page navigation!