1972 was hardly a ‘sterling’ year. The USA had just unilaterally terminated the convertibility to gold, and the world economy was struggling with the new system of freely convertible currencies. Inflation was on the rise, and so were commodity prices. Wages stagnated. The Vietnam War was going badly. Inchoate protest had spread from the fringes to society as a whole (see Public Philosophy: Essays on Morality in Politics by Michael J. Sandel). The prevailing whiggish view of inevitable historical progress looked increasingly frayed; self-doubt had spread together with social unrest.

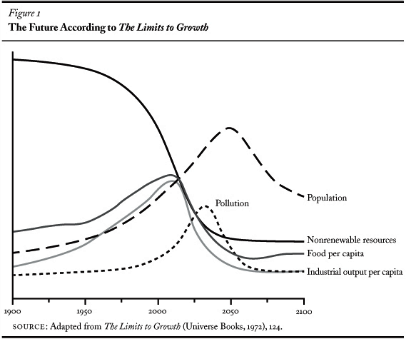

And then the Club of Rome published the report The Limits of Growth (LoG). Failing drastic self-restraint in consumption – the message was – LoG’s unassailable mathematical model unequivocally predicted the end of civilisation by the half of this century – or thereabouts. Civilisational catastrophe loomed just around the corner.

Religion tended to prophesise (and explain) civilisational catastrophes as consequence of moral behaviour. Nuclear arms after WWII shifted the threat of civilisational catastrophe into the realm of the political. LoG may have been the first time ever that man’s material activities were portrayed as the impending cause of a civilisational catastrophe – it was no longer a religious, but a secular issue. Given our propensity for analogies, one could have foretold the popularity of the argument.

Bjørn Lomborg has revisited this epochal publication in the latest issue of Foreign Affairs (see ‘Environmental Alarmism, Then and Now: The Club of Rome’s Problem – and Ours’ by Bjørn Lomborg). The article is written in a somewhat hectoring and strident tone. One best ignores the author’s style. Some of the points Lomborg is making are worth reflecting upon.

After crunching an untold number of equations, LoG pontificated: given (a) increasing shortages in agricultural land, (b) scarcity of non-renewable resources, (c) increasing population, and (d) pollution, the fifth factor – industrial production – would be sacrificed in a desperate and futile attempt to feed the world. To no avail: ‘The only hope to avoid a civilisational collapse, the authors argued, was through draconian policies that forced people to have fewer children and cut back on their consumption, stabilising society at a level that would be significantly poorer than the present one,’ Lomborg sums up.

Looking at the LoG predictions in the light of hindsight, the results are truly disappointing. We are far from the poorhouse. The last forty years have marked significant (if not adequate) human progress in about all statistics of human development. And the future looks bright, if somewhat hotter. (How far we have travelled in this respect may be gleaned from the fact that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, for example, the only major group to have set out informed GDP scenarios through 2100, estimates that global GDP per capita will increase fourteenfold over the century and increase twenty-fourfold in the developing world.)

Admittedly, it was the very beginning of the ‘modelling era’. One might make allowances for neophyte’s errors and argue that the study was merely wrong in its timing, not in its predicted scenario. I can hear people muttering: ‘Sure, we got away with it by the skin of our teeth. But next time…!’ We enter here the murky area of yearly announcements that ‘the end of the world is ten years from now’.

Lomborg puts down the dismal failure to the modellers’ inability to forecast ‘human ingenuity’. The term is vague – his examples point to technology and individual creativity. He concludes: ‘None of this means that the earth and its resources are not finite. But it does suggest that the amount of resources that can ultimately be generated with the help of human ingenuity is far beyond what human consumption requires.’ This seems a bit triumphalist to me.

I’d rather use ‘enablers’ instead.

Enablers and the open world

Enablers are propensities – not inevitabilities like mechanical laws. Technology – an invention or a new production process – is clearly an ‘enabler’. Mindsets too are enablers (see The Measure of Reality: Quantification and Western Society 1250–1600 by Alfred W. Crosby). Worldviews, ideologies, and social emotions are ‘enablers’ – they determine the horizon of the social imagination. Social structures too are ‘enablers’ – the way we organise society determines what we may be allowed to do as individuals and what we may achieve as a group. And, of course, the values we hold are ‘enablers’ – whether we prize education or homeliness, work or leisure, are important for the long-term success of a society. Enablers all work together; not by direction or coercion but by a complex mixture of persuasion and habituation – what Alexis de Tocqueville called ‘the slow and quiet action of society upon itself’.

There are many other such ‘hidden movers’ whose effects we only dimly perceive. Common to enablers is that they may lie dormant for ages – in evolution it is easily millions of years – until circumstances bring them to the fore (take inventions, Lomborg’s drivers: they may lie dormant for centuries, and then spread in a wildfire of innovation and adoption). Consequently, the list of ‘enablers’ is never complete.

Underlying LoG is a tight network of ‘known’ and measurable mechanistic inevitabilities. One may tweak the parameters here and there, but not the structure: the outcome is inherent in the model, hence predetermined. In Micawberian fashion, LoG’s premises predict inevitable outcomes.

LoG is a ‘closed’ and ineluctable system – the Ancients called it ‘Procrustes’ Bed’. A dispositional world of ‘enablers’, on the other hand, yields an ‘open’ system with many possibilities and contingencies. Though I suspect I may have hotly espoused LoG at the time (I can’t remember), today my take is that, for good or bad, mankind will always surprise us in novel ways.

Did the emotional success of LoG rest on its character of imminent ‘catastrophe foretold’? I’d suspect it did: it may have satisfied deep guilt feelings in an opulent society already destabilised by the threat of terminal nuclear catastrophe. After an initial impact LoG faded from consciousness. Its effects lingered – unspoken. It enabled secular ‘catastrophic thinking’.

Lomborg has much to say about this new mindset, and I’ll outline and comment on it in a next post.

The post was first published on DeepDip.

Explore more of Aldo Matteucci’s insights on the Ask Aldo chatbot.

Click to show page navigation!